"The Stalin in the Soul": How Authors Become Their Own Censors to Please the Market

Reviewing Ursula K. Le Guin's Most Dangerous Essay

How I Compromised My Vision

Two years ago, I “retired” from my 190k subscriber YouTube channel. It’s called The Pop Song Professor (PSP), and it’s still there. I visit and post a video occasionally, but thinking about it saddens me because I failed myself and my fans

At first, I did short, scripted explanations of popular song lyrics. I got a bit of attention thanks to an underserved niche and a similar, successful blog I’d created. But when I explained songs by The Weeknd and Twenty One Pilots, my videos got tens of thousands of views, and within a couple of years I had 100,000 subscribers.

But I was my own greatest enemy

My vision had been to treat lyrics like poetry, to help viewers think about what they were listening to. I wanted to bring English class to Spotify. But my financial goal was to make at least $50k/year, which would have been enough to let me quit a company I was desperate to leave.

So instead of sticking to my vision, I focused 80% of my content on The Weeknd and Twenty One Pilots because those videos did best. I grew faster at first, but eventually the audience I had grown only cared about those two artists. Explanations of other artists rarely performed well because my main audience didn’t care as much. And I ran out of songs to explain by The Weeknd and Twenty One Pilots.

Frustrated, I tried other formats I thought would go viral—video essays, gameshows, listicles, lyric writing how-to’s, skits, etc. Soon I was juggling 10 different video series. My channel became so splintered by these attempts to please the market that soon it wasn’t clear to anyone (including myself) what I actually did.

I like to imagine that if I’d stuck with simple song explanations and worked on doing a better and better job of that, my channel would have succeeded more, and I’d have enjoyed the process more. But I burned out (a few times). And I decided to move on from PSP. I had achieved neither my vision nor my financial goal.

My experience with PSP comes to mind when I read Ursula K. Le Guin’s (UKLG) essay “The Stalin in the Soul” about a similar trap writers fall into.

Zamyatin’s Story

First UKLG gives the example of Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin (1884-1937) who was beaten, arrested, and imprisoned for dissenting with the Soviet Union. Despite all this, he penned one of the most subversive dystopian sci-fi novels ever written. We was highly critical of the Soviets and was banned from publication in Russia until 1988, so Zamyatin had to publish it in English in 1924.

The story depicts a totalitarian regime that controls every minute of its citizens’ lives. Even their names are replaced with numbers. But when the main character, D-503, interacts with the mysterious I-330, he learns of a rebellion and has the chance to think for himself.

Zamyatin would have been much more successful in his lifetime if he’d complied with Soviet policies and censors, but he stayed true to his personal vision and morals. And as a result, he wrote something truly powerful that directly inspired George Orwell’s 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, UKLG’s The Dispossessed, Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano, and countless more.

UKLG uses Zamyatin’s story to show what uncompromising artistry looks like. Zamyatin wasn’t concerned with pleasing people or discouraged by the threat of imprisonment. He stuck to his artistic vision.

The Compromising Author

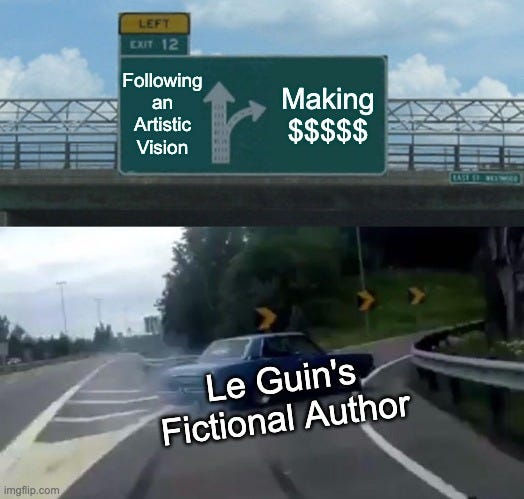

Later in “The Stalin in the Soul,” UKLG contrasts Zamyatin with the story of a fictional American author who accepts a more subtle form of censorship.

This author dreams of writing a powerful novel that will be challenging and interesting and profound.

But he rationalizes that he has to make money, so in a series of alternate paths UKLG shows him start his career by writing pulp fiction, porn, cheap comics, or low-quality movie scripts. In each, he makes good money and keeps telling himself he’ll write his dream novel eventually, but he never does. He dies wealthy but having produced nothing of lasting value, and he is quickly forgotten.

UKLG’s assertion is that “he accepted the judgment of the censor. He accepted, unquestioning, the values of his society.” He let the market decide what he was going to write. And if he had stuck to his original vision, he might have both written something lasting and made good money, but he compromised for the sake of quick commercial success.

The Market as Censor

And this is UKLG’s point in “The Stalin in the Soul”: Many authors don’t realize they are accepting a form of censorship when they write to market.

She writes, “It is all so painless. It is still more difficult to understand that one may be censoring oneself, extensively, ruthlessly—because that act of self-censorship is called, with full social approval, ‘writing for a market’. . . .”

And as UKLG notes, “The only standard, in the marketplace, is Will it sell?”

Market-censored authors aren’t concerned with the truth, beauty, goodness, or unity of what they write (unless they think those things will correlate to more money). If they could get paid for sitting on their keyboard, one imagines them jumping at the chance.

And that’s because the market-censored author is willing to compromise anything for the opportunity to make money writing—to become a professional author. Is paranormal romance popular? Let’s write that. Are love triangles popular? Let’s right those. Are books in one’s genre all 90,000 words? Let’s cut vital parts of the story to be more sellable. The market-censored author has little courage or sense of self.

And UKLG says the publishing industry rewards this kind of writing because it wants “products to sell, quick turnover, built-in obsolescence. They do not want large, durable, real, frightening things.”

The book industry thrives on trends (see: “built-in obsolescence”) based on “products” that are easy to understand, easy to package, easy to market, and easy to sell. And heaven forbid these stories challenge or grow or question (or cause their audience to do likewise): “Shock them, jolt them, titillate them, make them writhe and squeal—but do not make them think. If they think, they may not come back to buy the next can of soup.”

But UKLG argues that this problem is the joint responsibility of authors AND readers: “We writers fail to write seriously because we’re afraid—for good cause—that it won’t sell. And as readers we fail to discriminate; we accept passively what is for sale in the marketplace; we buy it, read it, and forget it. We are mere ‘viewers’ and ‘consumers,’ not readers at all.”

Is This Really a Problem?

It depends on what you want. If you’re satisfied with forgettable stories, escapism, and cheap thrills, you wont’ have to look far.

If you, an author, want to change lives or to be remembered, you can’t compromise.

If you, a reader, want stories that will change your life, you have to find authors who will challenge you and not just write what you and the market want.

As the Pop Song Professor, I should have kept to my vision of empowering my viewers to go deeper with lyrics. UKLG’s fictional author should have written his novel and said, “No,” to the short term money.

UKLG writes, “If art is seen as sport, without moral significance, or if it is seen as a self-expression, without rational significance, or if it is seen as a marketable commodity, without social significance, then anything goes” but “if art is taken seriously by its creators or consumers, the possibility of the truly revolutionary reappears.”

We need to look to the example of Zamyatin who took seriously the power in story and the power in his own vision. He had something worth saying, and he said it regardless of consequences.

If we can do that, we authors can write immortal stories with what UKLG elsewhere calls “moral resonance” that change lives. And readers who read these stories can grow and become richer, fuller people.

If we’re not writing and reading stories like those, why bother?

Thanks for reading past the dragon!

This essay was shorter and more difficult to write than my previous ones due (A) to not knowing where I wanted it to end and (B) to being very busy this last week. But it was worth it, and I hope I’ve encouraged writers and readers to do something meaningful.

If you’ve written or are writing a book against market preferences, please share it. And if you’ve read a book that sold poorly but that changed you, please share that! I always need more books on my ThriftBooks wishlist regardless of what my wife says.

I'm currently writing crime novels set in my locale, which is a tourist haven. I am writing in a popular genre aimed at mainly a summer reads audience. And I am toning down the violence and swearing about 20%, to make the books more palatable for that audience. It's working: I'm selling lots of books and I am not regretting it a bit. But I am sneaking in social criticism and questioning the skewed priorities of tourist havens. I don't believe that my books are disposable escapism, and I don't believe that there is a stark divide between being an artist and selling books. I never had any ambitions to write literary fiction but that doesn't mean I don't pursue perfection of my craft and that my books are empty of meaning.

A useful book on this subject is Joseph Bottum's The Decline of the Novel. In it he points out that the novel has ceased to play any role in public intellectual life. He refers to what he calls the Cocktail Party Test and asks what book you would be embarrassed to turn up to a cocktail party without having read. He suggests that the last such book was Bonfire of the Vanities in 1987. "If novelists themselves don't believe there exists a deep structure of morality and manners that can be discerned by the novel," he writes, "why should readers believe it?"

Getting novelists to believe it again is one thing. Getting readers to believe it again is something else entirely.