The True Difference between Sci-Fi and Fantasy That No One Talks About

And what it means for Star Wars...

A young man learns he has access to a mystical power. His home is attacked by evil, otherworldly forces. A wise guide shows him the way forward. He joins the good guys’ underdog team. He destroys the symbolic incarnation of evil.

Lord of the Rings? The Wheel of Time?

Sure, but I was describing Star Wars. When you step back, it sounds like fantasy doesn’t it?

“But, wait!” someone says. “If I know anything, I know Star Wars is sci-fi, NOT fantasy! There are spaceships and laser guns and aliens and—and—and…”

I understand the panic. Let’s back up: What is sci-fi? What is fantasy?

Everyone’s got an answer, but I trust few people to distinguish them more than Ursula K. Le Guin who wrote genre-defining fantasy stories (A Wizard of Earthsea, The Beginning Place, etc.) and genre-defying sci-fi stories (The Left Hand of Darkness, The Word for World is Forest, etc.) of the highest quality. She was one of the most influential and thought-provoking SFF authors to ever pick up the pen.

And in her collection of essays The Language of the Night, she defends science-fiction/fantasy (SFF) as genres, defines them, and argues we should raise standards for our SFF both as readers and writers. If you care about these two genres, reading The Language of Night feels like drinking cold water on a Vegas summer day (the forecast here is 108°F today).

But what does UKLG say is the difference between Sci-fi and Fantasy?

I’ll give you a hint: it’s not whether a story has time travel or magic spells or unicorns or bug monsters from Mars. Those are the outward trappings of SFF—the seasoning on the steak, not the steak itself.

According to UKLG’s definitions, the differences stem from the role of each in our collective social mindset—the spirit and purpose of the genres.

Science Fiction: Human-Focused Thought Experiments

In her introduction to her 1976 novel The Left Hand of Darkness (TLHOD), UKLG writes, “All fiction is metaphor. Science fiction is a metaphor. What sets it apart from older forms of fiction seems to be its use of new metaphors...”

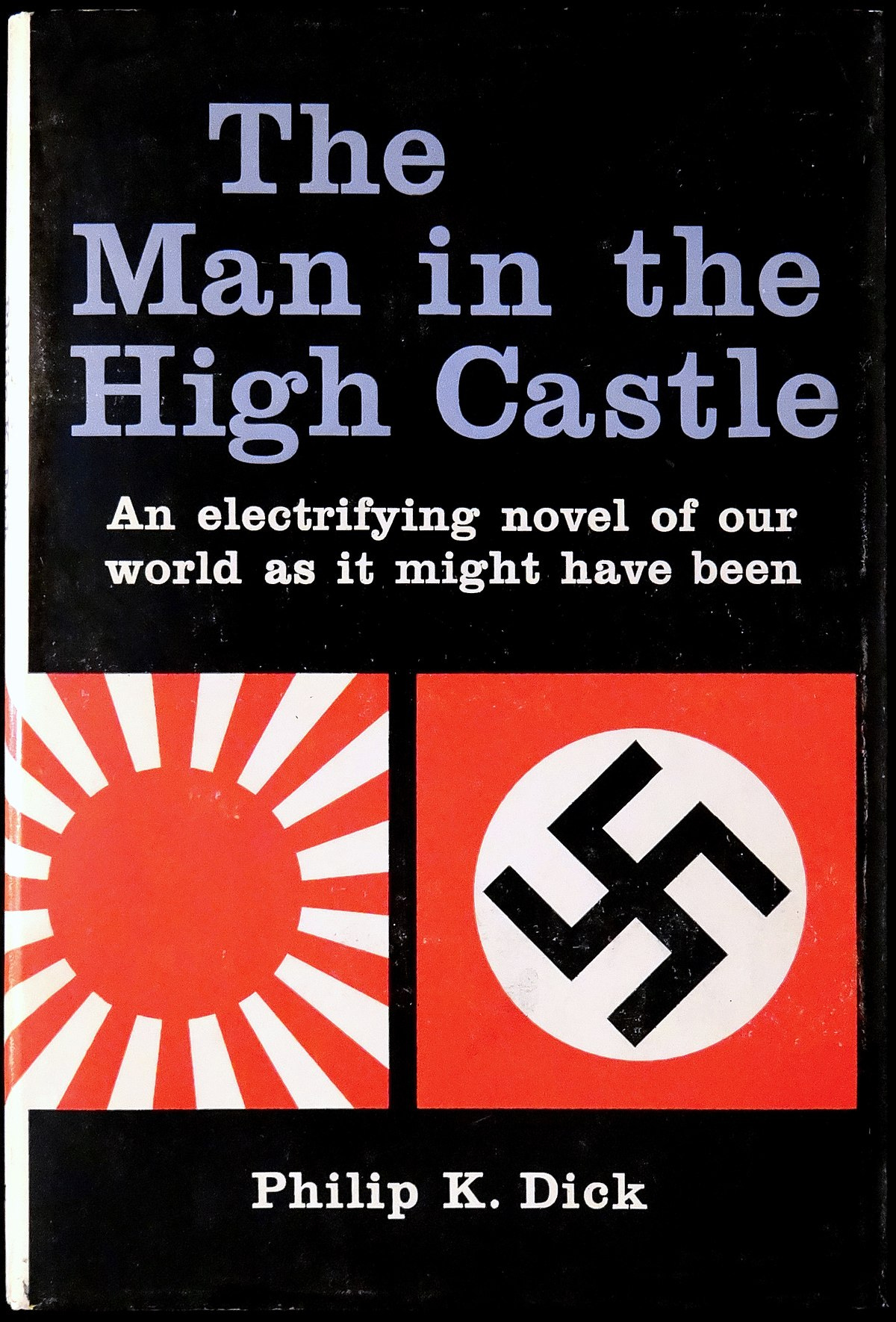

Mary Shelley published the first sci-fi novel Frankenstein in 1818 when science was advancing rapidly; she asked if man should play God. After the rise of industrialism—man seemingly conquering nature with machines—H. G. Wells wrote The Time Machine in 1895 and showed man conquering time with a machine. After World War II, in The Man in the High Castle, Philip K. Dick asked what would have happened if American had not joined World War II.

We haven’t lacked for speculative sci-fi topics these last two hundred years, and today we have AI, robotics, social media, drone warfare, and dozens more to choose from. The opportunities present themselves faster than we can write them.

When Le Guin started writing sci-fi, critics tended to ignore or pan the genre. But Le Guin saw the power in sci-fi and argued vehemently for writers to write well and readers to have high standards. She knew if the genre took itself more seriously, these stories could change lives and become some of the most influential books ever written.

This made her frustrated with writers and readers who only wanted flashy stories from pulp magazines about sci-fi tropes. In her 1975 essay “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown,” she says, “Science fiction has mostly settled for pseudo-objective listing of marvels and wonders and horrors which illuminate nothing beyond themselves and are without real moral resonance: daydreams, wishful thinking, and nightmares.” Authors were writing sci-fi stories about space and laser guns and aliens and new technology but with no purpose beyond novelty and passionless entertainment.

In another essay (that I’m unable to relocate), she refers to these writers as “hacks” who lack an ethical approach to storytelling.

So we know what not to do. What does UKLG say we should do?

We see part of her definition of what popular sci-fi tended to do in TLHOD: “the science fiction writer is supposed to take a trend or phenomenon of the here and now, purify and intensify it for dramatic effect, and extend it into the future.”1

This extrapolation makes sci-fi fun. It’s asking, “What if?” What if someone did invent a time machine? What if Germany and Japan had won World War II? What if we lived real life in VR? What if social status was determined by a peer rating system?

And this might sound a lot like just sprinkling in a few laser guns or some space travel and calling it a day—the lazy writing we’re supposed to avoid—but UKLG’s approach goes deeper. In 1976 in “Is Gender Necessary,” she writes “One of the essential functions of science fiction, I think, is precisely this kind of question-asking: reversals of a habitual way of thinking, metaphors for what our language has no words for yet, experiments in imagination.” Sci-fi isn’t about the trappings; it’s about running thought experiments.

But experiments in what context? Where do they take place?

UKLG doesn’t address this directly, but it’s heavily implied in her work and near universal in the greatest sci-fi works that the extrapolation and experiments begin in our own world. Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot collection takes place late in our twenty-first century. His Foundations series and Le Guin’s Haimish Cycle take place in our far, far future. The Man in the High Castle takes place in alternate history that veers from ours during World War II.

Almost universally in sci-fi stories, the setting is an alternate or future version of our own. The extrapolations and experiments stem from our own world. They are experiments on us.

However, good sci-fi doesn’t stop at sight-seeing trips of “what could (have) happen(ed).” In her 1975 essay “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown,” UKLG writes, “At the heart of [a novel] you will not find an idea, or an inspirational message, or even a stone ax, but something much frailer and obscurer and more complex: a person.”

That’s because, according to her, good writing is driven by “Characters. Round, solid, knobby. Human beings, with angles and protuberances to them, hard parts and soft parts, depths and heights.”

When UKLG was growing up, American sci-fi focused almost entirely on “the invention of miraculous gadgets, the relation of alternate histories, and so on”—the tropes and trappings of science-fiction—with two-dimensional, empty characters to prop them up. Often these were busty, blonde women sans personality kidnapped by aliens or muscular, emotionless space captains coming to the rescue.

These characters couldn’t support true thought experiments or analysis of the effects of sci-fi subject material; there was no substance to the characters themselves. Good sci-fi has to run these experiments on characters who are as close to real people (see: believable characters) as possible.

In “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown,” UKLG asks herself whether it is “advisable or desirable that the science fiction writer be also a novelist of character?” She responds, “This, to me, is the whole point.” Without good characters, sci-fi isn’t sci-fi. It’s a pastiche of sci-fi-ish things.

But I digress, and because I’m having a hard time bringing this to a close, I’ll sum it this way: true sci-fi is extrapolated social and technological trends and modernistic thought experiments set in our own world and seen through the eyes of fully-fleshed, believable characters.

Fantasy: Seeing Ourselves in the Unfamiliar

In “Do-It-Yourself Cosmology” from 1977, Le Guin suggests that sci-fi is an extraverted form of fantasy because of its external object—the big what-if’s it considers. On the other hand, she says the “original and instinctive movement of fantasy is, of course, inward.” And in “The Child and the Shadow” from 1974, she writes, “Fantasy is the language of the inner self.”

Fantasy stories aren’t meant to be an exhibition of other-worldly wonders like unicorns and dragons and epic magical battles. They use these wonders to dive into the psyches of readers and authors. They isolate a bit of the human experience and place it in a new setting so we can understand ourselves better. This is what it’s been doing since The Epic of Gilgamesh and the plays of ancient Greece.

In Neverwhere, Neil Gaiman’s fantastical London-Below environment challenges the self-doubt of main character Richard Mayhew who must learn to respect himself. He was able to get by in the real world, but being slung into the chaotic London-Below requires him to stand up for himself.

In other fantasy books, we see the whimsy we’re missing in our own world (Alice in Wonderland). We analyze the temptation to power (Lord of the Rings). And we find what it means to hope for something (The Horse and His Boy).

These books are valuable because we humans often grow blind to what’s in front of us. We take virtue for granted. We don’t appreciate the adventure in our lives. We lose the sense of wonder and curiosity we had as children. We become too familiar with our own world and thus numb to what’s really there. But the fantasy writer has the extraordinary power (and responsibility) to use magical elements to make aspects of our own world come alive to us again.

Examples of this include talking animals in Aesop’s Fables that take on unique human characteristics (ants = hard working), powerful witches in The Brothers Grimm who might represent chaos and entropy in a dangerous world, or the ancient gods in Greek myths who each represent half a dozen different things (though mostly vanity and selfishness).

Fantasy puts the common into fantastical worlds so that we can see the fantastical in our seemingly common world.

A textbook example of this is UKLG’s A Wizard of Earthsea. In it, Ged, a young wizard, accidentally unleashes his shadow—a dark embodiment of all that is ugly and evil in himself. Ged’s shadow, which represents his dark side or his capacity for evil, seeks to kill and replace him.

Le Guin references this explicitly in “The Child and the Shadow,” her defense of fantasy stories, when she writes, “When you look at the story as a psychic journey, you see something quite different, and very strange. You see then a group of bright figures, each one with its black shadow. Against the Elves, the Orcs. Against Aragorn the Black Rider. Against Gandalf, Saruman. And above all, against Frodo, Gollum. Against him—and with him.”2

She sees Tolkien doing what she does in A Wizard of Earthsea: cutting straight through the human experience to give metaphor and form to the essential battle of good versus evil. She writes that “fantasy is the natural, the appropriate language for the recounting of the spiritual journey and the struggle of good and evil in the soul.”

And the power of fantasy stories is that they recount this struggle symbolically—their unreality frees us from assumptions we might have if we read fiction set in our world and opens us to looking at themes in a new way. The “great fantasies, myths, and tales . . . speak from the unconscious to the unconscious. . . . they short-circuit verbal reasoning, and go straight to the thoughts that lie too deep to utter.” But cutting this deep is not easy, and she believed that “to live in the real world, I must withdraw my projections; I must admit that the hateful, the evil, exists within myself.”3

Once that’s done—once we’ve plunged into the self (or while we are plunging into it)—the fantasy author can begin writing. Fantasy isn’t actually about epic quests to far away magical lands. It’s about the much more interesting and much more difficult journey inward.

By placing the familiar, the confusing, and the forgotten into the magically unfamiliar, good fantasy reacquaints us with the concept or idea in our own world. It’s a bit on the nose, but in C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, Aslan says, “In your world, I have another name. You must learn to know me by it. That was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.”

Doesn’t that say it all?

When we finish a good fantasy story, having been jolted awake by the journey to Faerie on which we met an aspect of ourselves in a new guise, we should be prepared to return to our own world changed and better (even if we can’t explain why).

Le Guin says, “What we need to grow up is reality, the wholeness which exceeds human virtue and vice. We need knowledge; we need self-knowledge. We need to see ourselves and the shadows we cast.” And according to her, the purpose and definition of fantasy stories is doing just this in an unfamiliar, magical setting.

So Is Star Wars Sci-fi?

If we’re looking at the trappings and empty symbols and tropes of science-fiction, Star Wars is indeed science fiction; there are lasers and space travel and aliens. But if we’re looking for the purpose of science-fiction, Star Wars is clearly missing something. It does not focus on an extrapolative change or a thought experiment told through the eyes of its characters.

Rather, Star Wars explores deeper human elements in an unfamiliar world. In A New Hope, Luke grows up, he sacrifices for friends, and he learns to control his own emotions. And we view all of these things through the lens of “a galaxy far, far away.”

Ergo, Star Wars is a fantasy.

Thanks for reading past the dragon!

Writing this essay was so hard, and I know it’s not perfect yet. It was difficult to say the things I wanted to to say. But the result was worth the effort, and I hope you’ve enjoyed it.

Please share a novel you love that truly fits the sci-fi or fantasy definitions above. If a book accomplishes these things, it needs to go on my Thrift Books wishlist.

As Maximilian notes in the comments, Le Guin wanted sci-fi to be more than this.

While it aligns with my point, I don’t think Le Guin does Tolkien justice here. I doubt Tolkien would have really liked the implied comparison to dualism when his faith led him to see evil, not as an equal and opposite force to good, but as a corruption of it (orcs are only corrupted elves after all). In Tolkien’s worldview and writing, the Fellowship and its members weren’t simply good. The Fellowship itself was full of evil. Boromir succumbed to his pride. Gandalf knew the temptation of the Ring would be too great for him. Frodo gave in in the end. Legolas and Gimli were both racists at first, etc. Le Guin gets the closest to recognizing this when she writes when referring to Frodo that Gollum was “with him.” It would have been more accurate to Tolkien, I think, to say “within him.”

She’s more in line with Tolkien here.