Escapists and Intellectualists Can't Experience True Literary Joy

Unless they stop "using" books...

In John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, the main character, Christian, must pass a test of faith by walking between two supposedly chained-up lions.

The lions roar and slash their paws at him, but Christian makes it through and can continue down the path to the Celestial City.

This sequence is a perfect metaphor for reading well because two lions guard that path as well. The lion chained to the left is escapism. The lion chained to the right is intellectualism.1 And if a reader doesn’t stick to the narrow path between, their literary efforts will bring them nothing.

These lions represent two traps I see most readers fall into—traps that ruin the reading of a good book and that keep us from receiving what that book has to offer.

To explain, I’ll enlist the help of C. S. Lewis and his little-known literary theory book An Experiment in Criticism. Lewis published An Experiment in Criticism in 1961, and the experiment therein flips literary criticism on its head. He wonders “how far it might be plausible to define a good book as a book which is read in one way, and a bad book as a book which is read in another.” What would happen if instead of judging books on their own literary merits, we observed the kinds of readers and reading experiences specific books encouraged?

The right kind of reader (the “literary” Lewis calls them) approaches a book disinterestedly and opens themselves to step into the author’s and characters’ perspective:

“The first reading of some literary work is often, to the literary, an experience so momentous that only experiences of love, religion, or bereavement can furnish a standard of comparison. Their whole consciousness is changed. They have become what they were not before.”

He writes later in the book that “this process can be described either as an enlargement or as a temporary annihilation of the self.” Uncle Screwtape of Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters describes true humility as “self-forgetfulness,” and in An Experiment in Criticism, Lewis writes, “The first demand any work of any art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way.”

According to Lewis, the literary reader goes humbly to a piece of art setting aside their own desires and preferences and opinions and subjective ideas (as best they can) so they can be open to new experiences, opinions, and perspectives. Only by abandoning the self can the self be enlarged.

It’s like the child who puts his hand in the cookie jar but can’t pull it out because he’s holding too many cookies. Another child who lets go of all but one cookie will be able to actually eat his cookie. And if he holds to this strategy—denying his greater ambition temporarily—he’ll eventually be able to eat all the cookies he wants.

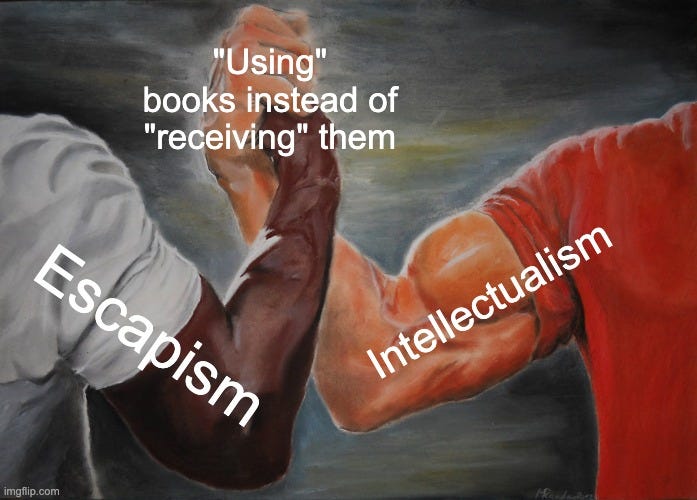

And this is the difference between the literary and the unliterary. Lewis writes, “The distinction can hardly be better expressed than by saying that the many [the unliterary] use art and the few [the literary] receive it.”

But how do the unliterary use art?

According to Lewis, they go into the reading experience having already decided what they want from it. They aren’t willing to set aside the self so that the story can show them something new.

What is the result of this kind of reading?

“When they have finished the story or the novel, nothing much, or nothing at all, seems to have happened to them.”

Based on An Experiment in Criticism, I believe Lewis’s unliterary readers fall to one of two unliterary lions: escapism or intellectualism.

Escapism: The Gluttonous, Lazy Lion

Lewis admits that “there is a clear sense in which all reading whatever is an escape.” We all go into that hazy-headed trance when we read a story for long enough. “It involves a temporary transference of the mind from our actual surroundings. . . .” But Lewis adds later, “By adding -ism to it, we suggest, I suppose, a confirmed habit of escaping too often, or for too long, or into the wrong things, or using escape as a substitute for action where action is appropriate, and thus neglecting real opportunities and evading real obligations.”

I don’t think escape is bad in small doses. Life is hard, and sometimes everyone need a break. My wife and I feel the need to “turn our brains off” at the end of the day sometimes. With children and jobs and a home and other responsibilities, it’s nice to not think about anything important or challenging for a moment. I usually cope with having to do dishes at the end of the day by watching sitcoms like The Office or reality shows like Taskmaster.

But when scanning BookTube or reading online, I’ve noticed a different approach to the word “escape.” These readers praise escape for escape’s sake as if though the point of literature and stories was to disconnect us from our lives.

And this is a terrible, terrible mistake because these readers deny the power of stories; they are trading something real and life changing for something shallow, temporary, and immediately forgotten.

Lewis gives us clues as to what an escapist reader looks like and how they read.

According to him, some unliterary readers “escape into egoistic castle-building. And this itself may be . . . harmless, if not very profitable. . . .”

The egoistic castle-builder gravitates to stories that invite them to imagine themselves as the hero and then shows that hero getting all the kinds of the things the reader might like—honor, riches, adventure, love, or even tragedies and catharsis. This is the escapist reader who likes books they can live their own dreams through vicariously. The easiest example might be people who only read stories about a specific romance trope like “friend-to-lovers” or “forced proximity.”

My favorite author who invites me to read like an escapist is Rafael Sabatini. He wrote adventure novels in the first half of the 20th century. In his most popular books (Scaramouche, The Sea Hawk, Captain Blood), the heroes are always confident, intelligent, deadly men of action. Obstacle after obstacle arises, and while the heroes are always at a disadvantage, they figure everything out brilliantly and look (very) cool doing it. Reading these books doesn’t do much besides pump me up with a false sense of bravado and confidence that doesn’t last. (But Scaramouche is still one of my favorite books of all time.)2

But like Lewis notes, this kind of escapism is “not very profitable.” And I’d argue (having experienced it with Sabatini and others) that egoistic castle-building is like candy. A little here and there is fine, but you can’t build a steady diet on it.

Lewis writes that “the unliterary reader wants only the Event,” which I take to mean plot-focused stories.

Escapists want to know what happens next, and they don’t want the story to muddle around. They “demand swift-moving narrative.” They tend to avoid character-driven stories and slow builds. Challenging stories leave them bored because they demand constant novelty and narrative progress. They are usually unwilling to wait for larger payoffs, and they gravitate to tropes they recognize and like.

“They are either quite unconscious of style, or even prefer books which we should think badly written.”

Lewis says the unliterary avoid anything with elevated or artfully constructed language, so poetry is right out. And “they never, uncompelled, read anything that is not narrative.” “They have no ears” for language. And “the hackneyed cliche for every appearance or emotion . . . is for him the best because it is immediately recognisable. ‘My blood ran cold’ is a heiroglyph for fear.”

More detailed analogies or description or beautifully written language requires the reader to pay attention to the words themselves, and this is undesirable for the unliterary reader because it requires more effort and distracts them from “the Event.”

They don’t expect to be changed by what they read.

Lewis gives an example of a man who “never expected [art] to be anything but transitory, and not very important, entertainment; he never dreamed that any art could provide more than this. He goes to the pictures not to learn but to relax. The idea that any of his opinions about the real world could be modified by what he saw there would seem to him preposterous.”

The unliterary reader labels all literature as entertainment because they don’t know they can get more out of it. And if a book is too challenging, they label it as “boring” or “bad entertainment.” They’re not interested in working with a book to achieve personal growth.

After all that, if you find it tempting to think Lewis was a “snob” who hated “entertainment” but exulted “art,” read this: “I would say that every book should be entertaining. A good book will be more; it must not be less. Entertainment, in this sense, is like a qualifying examination. If a fiction can’t provide even that, we may be excused from inquiry into its higher qualities.”

Unliterary readers have got one thing right that snobs sometimes mistake: a story must be enjoyable to read. If a piece of art doesn’t even bother to entertain us, Lewis tells us to write it off. Who cares? The author doesn’t care enough to write a book we’d want to read.

But if a book stops at entertaining escapism, Lewis tells us to ask for more. Yes, let’s escape to another world. Let’s be entertained. But let’s come back changed and better for it like the children in his Narnia adventures.3

Intellectualism: The Wiry, Insecure Lion

If you read Lewis’s indictments of escapists and chuckle at “the poor fools” instead of feeling sorry for them, the second lion—intellectualism—has you in its paws.

Recall that Lewis’s point of reading is to enlarge ourselves through self-annihilation—to find true joy in the reading experience.

But the person who reads for the sake of their own intelligence, knowledge, or self-aggrandizement fails to truly profit from reading as well.

Lewis was wary of people who read books to look smart, and he has several categories those readers fit into:

“The [literary] cannot be identified with the cognoscenti.”

“Cognoscenti” refers to people who are extremely knowledgeable about a certain topic, in this case, literary academics or book reviewers—people whose job it is to say and write smart things about books. They are prone to losing the pleasure of reading. These people often cannot afford to read for the joy of it or disinterestedly. “They are mere professionals.”

“Still less [a literary reader] is the status seeker.”

Lewis describes families in which reading is valued, and members take part in reading to keep up with what’s popular and fashionable (or especially controversial). For them, the entire point of reading is social. Lewis writes, “Yet, while this goes on downstairs, the only real literary experience in such a family may be occurring in a back bedroom where a small boy is reading Treasure Island under the bed-clothes by the light of an electric torch.”

“The devotee of culture is, as a person, worth much more than the status seeker.”

Lewis writes, “He reads as he also visits art galleries and concert rooms, not to make himself acceptable, but to improve himself, to develop his potentialities, to become a more complete man.”

I’m most tempted in this direction. I often choose books not because I am open to receiving what the novel has to say but because I want to check the box on a classic or “foundational” book. This motivation led me to read The Brothers Karamozov and Infinite Jest last year. Thankfully, both books were so powerful and rich that I couldn’t help but get lost in them.4

While the fashionable status seeker tends to read interesting newer books, the devotee of culture is “more likely to stick too exclusively to the ‘established authors’ of all periods and nations, ‘the best that has been thought and said in the world.’”

And yet, Lewis writes, “this worthy man may be, in the sense I am concerned with, no true lover of literature at all.” The devotee of culture reads books for the same reason we do push-ups. And I haven’t met anyone yet who does push-ups because they love them.

The moralist looking for lessons.

Lewis references the false “belief that all good books are good primarily because they give us knowledge, teach us ‘truths’ about ‘life.’” Authors are then “reverenced as teachers and insufficiently appreciated as artists.” This is the opposite of the escapist who finds preposterous “the idea that any of his opinions about the real world could be modified by what he saw” in art. These people can’t enjoy a story for its own sake because they’re looking for “the point.” Woe betide the story that has no obvious moral.

And finally the too-eager critic.

An Experiment in Criticism contests critics with high opinions of themselves who pan every book not “protected by the momentary critical ‘establishment.’” Lewis had noticed that as new critical theories came and went, different books were propped up as “the best books.” Certainly an ever changing canon was not a reliable one.

And many of these critics used books to advance their pet literary theories or to make themselves appear intelligent.

Lewis admits that “there is no work in which holes can’t be picked,” but he argues for a humbler approach to literature: if a book can be read well by at least one person, then that book has some literary value.

Lewis writes, “I want to convince people that adverse judgments are always the most hazardous, because I believe this is the truth.” His gamble is that if critics have to work extremely hard to pronounce a book “bad,” we might get more moderated criticism that focuses on praising good books and sending readers to them “with a good appetite.”5

These five approaches “fix the ultimate intention on oneself. [They] treat as a means something which must, while you play or read it, be accepted for its own sake.” Lewis originally meant that quote only for the devotee of culture, but it applies equally well to the others.

And, thus, you can see that these intellectuals do the same thing as the escapists. Instead of letting the work speak to them, they have already decided what they want from it. And whether those desires are helpful or vane, they mute the power of the reading experience.

The Path to Reading Well

Where does this leave us?

With an injunction no one ever wants to hear: We must humble ourselves.

If we are to read well, we have to read with an open mind.

Only then can we have the literary experience “so momentous that only experiences of love, religion, or bereavement can furnish a standard of comparison.”

If we want to escape or numb ourselves to the real world, we can. If we want to become smarter or to look smart, we can. But “then we are so busy doing things with the work that we give it too little chance to work on us. Thus increasingly we meet only ourselves.” And even though we may have read widely, the world we inhabit is as tiny as that of someone who doesn’t read at all.6

If we humble ourselves or temporarily annihilate our own self interest when we read, we can make it past these lions and on to the heart of the book.

Only then are we able “to see with other eyes, to imagine with other imaginations, to feel with other hearts, as well as with our own” and to come back “enlarged.”

Thanks for reading past the dragon!

I really enjoyed writing this essay and getting to revisit An Experiment Criticism. I almost wish I’d decided to write my masters thesis on this book.

Please share a book you loved that you read the first time without a desire for escapism or intellectualism. Maybe a book you went into with no expectations of and ended up loving. I need more books on my ThriftBooks wishlist.

If you want to rename them “excessive escapism” or “excessive intellectualism,” I won’t contest it. If I wasn’t worried about being pithy, I’d name them “escapism for escapism’s sake” and “intellectualism for intellectualism’s sake.”

I’m not sure Scaramouche is completely without value. I just haven’t taken the time yet to properly assess it. I’ll need to read it again. Oh, no! Don’t twist my arm.

The Pevensies’ adventure to Narnia is basically a meta-description of what good reading of good fantasy does for you. I think any kind of portal fantasy is really.

I was also so confused by them that I just had to take what I could get from the experience and dive deep into the joy of the story.

My wife points out that this would also make readers less likely to avoid books because of the fear of looking stupid.

Lewis’s quote that I’m referencing: “Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realise the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors. We realise it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated.”

I noticed Anathem in your list; a good book.

Might I recommend Cryptonomicon by the same author.

This article GETS it. Thank you so much for introducing us to this work of Lewis's. I've been struggling for some time to articulate these ideas to my friends, and to see them here laid out in such clarity is a relief and a joy all at once, haha -- the problem of excessive escapism and excessive intellectualism is still as common today as in Lewis's time, it seems.