Good Fantasy Makes the Real World Better

Pt. 2 on Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories" with Eric Falden: Recovery

Welcome to Week Two of and I dissecting J. R. R. Tolkien’s 1947 essay “On Fairy Stories.” Last week Eric discussed what Fantasy meant to Tolkien and why good world building is vital to suspension of disbelief. I highly recommend you read that before proceeding.

Fantasy stories or, as Tolkien calls them, “Fairy Stories,” often promote virtues like courage, loyalty, honor, and sacrifice. But according to Tolkien, there are meta virtues inherent to the way Fantasy is written due to its focus on the otherworldly. He holds that effective Fantasy provides three overarching benefits to readers: Recovery, Escape, and Consolation. This week, let’s tackle Recovery.

When I was seven and living in North Carolina, I loved the woods behind my house. As far as I could see, there were rows of tall, thin pine trees. Bright green, fluffy ferns grew between them, and the floor was a springy mat of brown pine needles. Far away, I could see brooding houses dark in the pine tree shade. These huge, mysterious woods fascinated me, and I loved them.

When we moved a year later, I kept exploring. I discovered the Gecko Tree (full of geckos) in Okinawa; giant pre-construction piles of dirt in Virginia that I pretended were Mordor; and steep, forested hills in Washington that led down to the Puget Sound (and an honest-to-goodness run-aground, cement ship I would climb into at low tide).

When I turned sixteen, my family moved back to our home in North Carolina. But the woods—they were tiny! The trees weren’t grand or tall. The ferns were sparse. The houses deep in the woods were close enough to throw a rock at.

The woods hadn’t shrunk. I had grown. They had only seemed grand because I had been so small, and now I was thirty inches taller. In that moment, all the mystery and wonder of that forest evaporated. And I didn’t bother to explore them any more.

This experience is called Demystification, an event whereby the unfamiliar becomes familiar. The confusing becomes clear. The complicated becomes simple. And the grandiose becomes small. Demystification is like getting a suspenseful book spoiled and not having a reason to keep reading.

Tolkien describes demystified things as1. . .

[T]he things which once attracted us by their glitter, or their colour, or their shape, and we laid hands on them, and then locked them in our hoard, acquired them, and acquiring ceased to look at them.

My growth and experience had caused me to see the forest with what Tolkien calls the “the drab blur of triteness or familiarity” or “possessiveness.” When we become overfamiliar with something we were once amazed by, we come to feel (in a sense) that we own it. And when we own it, we take it for granted, and it loses any magic it had.

Another example would be of a person who plants a garden by their front walk and, after a few days, stops looking at the flowers. Or a married couple who, after a few years, doesn’t spontaneously notice how attractive their spouse is. Or the child who gets a new toy and can’t be bothered with it after a few hours.2

I think humankind likes to do this on a larger scale too. The Ancient Greeks (to an extent), Enlightenment thinkers, literary Realists, and Modern scientists (as I describe in my essay on the historical eras of Fantasy literature), thrived on Demystification. By reducing the universe to what was “real” (or what they could physically sense) and trying to take ownership over it, they made great advances in technology, medicine, politics, and philosophy.

But when you gain something, you also lose something. My favorite example comes from C. S. Lewis’s 1955 Surprised by Joy:

The truest and most horrible claim made for [the automobile] is that it ‘annihilates space.’ It does. It annihilates one of the most glorious gifts we have been given. It is a vile inflation which lowers the value of distance, so that a modern boy travels a hundred miles with less sense of liberation and pilgrimage and adventure than his grandfather got from traveling ten.3

The car demystified traveling. What was once an adventure became an inconvenience. This is how demystification works—in the pursuit of novelty or progress or just by means of boredom, we cease to see magic where we once did. And it is an inevitable time of life. But that doesn’t mean we can’t do anything about it.

Tolkien proposes a solution: Recovery. In “On Fairy Stories,” he calls it the “regaining of a clear view” or “seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them.” Essentially, Recovery is about helping readers of Fairy Stories (or Fantasy) to recapture the feeling of wonder for things they now take for granted.

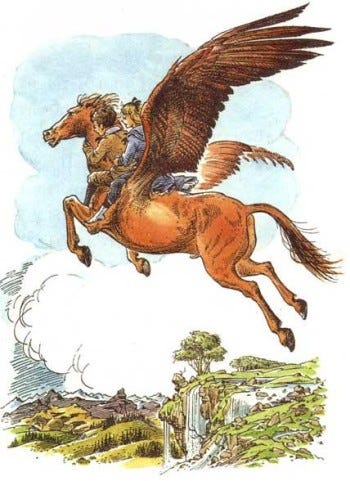

He writes, “By the forging of Gram4 cold iron was revealed; by the making of Pegasus horses were ennobled; in the Trees of the Sun and Moon root and stock, flower and fruit are manifested in glory.”

All these fantastical things help us to again see the wonder of the material things they are based in. And the world building and narrative surrounding them serve to contextualize that regaining of magic.

Tolkien sees fit to clarify that what he is describing is NOT defamiliarization—the process whereby something familiar becomes alien so that we notice it again. Defamiliarization was a literary technique Russian Formalists explored in the early 1900s, but it’s also found, as Tolkien notes, in the work of Charles Dickens and G. K. Chesterton where it’s known as “Mooreeffoc.”

In a discarded shred of an attempted autobiography (later published in Life of Dickens (1872)) Dickens writes this:

In the door there was an oval glass plate, with COFFEE-ROOM painted on it, addressed towards the street. If I ever find myself in a very different kind of coffee-room now, but where there is such an inscription on glass, and read it backward on the wrong side MOOREEFFOC (as I often used to do then…) a shock goes through my blood.

Chesterton (who was a Dickens scholar) adopted this strategy in The Everlasting Man (1925) (and many other places). He writes that someone “has said that a fine man on a fine horse is the noblest bodily object in the world.” He then considers “a man [who] has got into a mood in which he is not able to feel this sort of wonder” (i.e. a person for whom horse and rider are demystified).

Chesterton advocates shocking the man with a Mooreeffocish approach so that he can Recover that sense of wonder: “he will not be able to look at a horse or a horseman at all until he has seen the whole thing as a thing entirely unfamiliar and almost unearthly.”

Chesterton goes about this by describing the horse as “one of the very queerest of the prehistoric creatures” coming out of an ancient cave with a “strangely small head set on a neck not only longer but thicker than itself, as the face of a gargoyle is thrust out upon a gutter-spout, the one disproportionate crest of hair running along the ridge of that heavy neck like a beard in the wrong place” and so on.

Chesterton’s point is that once the demystified man appreciates how odd a horse is and how odd the impulse to ride it is, only then can he again be awed by the sight of horse and rider.

Chesterton often used Mooreeffoc to shock his readers into refreshing their view of the world, and (while Dickens’s goal rarely progressed beyond just shocking) that makes his use very similar to how Tolkien uses Recovery in Fantasy.

Tolkien doesn’t seem to want to admit this (for some finicky, fussy Tolkien-esque reason5) and writes that Mooreeffoc can make something seem “alien,” “but it cannot do more than that.” Of course, Chesterton calls this statement into question by often using this sense of strangeness to Recover the wonder of a thing. Throughout his body of work, Chesterton uses a Mooreeffocish approach to reawaken us to the beauty of horses, marriage, home, cheese, alcohol, solitude, arguing, postmen, doodling, and much more.6 Thus even Mooreeffoc, handled well, can aid Recovery and help us see “things as we are (or were) meant to see them.”

But Tolkien approaches Recovery through the more holistic and complicated genre of Fairy Stories:

Creative fantasy, because it is mainly trying to do something else (make something new), may open your hoard and let all the locked things fly away like cage-birds. The gems all turn into flowers or flames, and you will be warned that all you had (or knew) was dangerous and potent, not really effectively chained, free and wild; no more yours than they were you.

Instead of making things seem strange and leaving it at that (like Dickens’s Mooreeffoc) or using the strange to revive our view of something (like Chesterton), Fairy Stories can bring new life to the banal. They help us realize that what we’d become familiar with and forgotten, we had totally misunderstood. The things we thought were cold, lifeless treasures are really flowers and flames and escaping birds—alive and beautiful things that we cannot control or fully understand.

It bears repeating what Tolkien wrote: “By the forging of Gram cold iron was revealed; by the making of Pegasus horses were ennobled; in the Trees of the Sun and Moon root and stock, flower and fruit are manifested in glory.”

By the growing of Ents, trees gain solemnity. By the simplicity of the Hobbit life, hearty food and ale gain enchantment. Through the dragon inside of the Lonely Mountain, all mountains become adventurous destinations.

I was able to Recover the sense of awe and excitement in my Demystified woods thanks to foam boffer swords7 and airsoft guns. When the woods became a battlefield and a place for adventures, they became wild again, and the draw to explore them regrew. They escaped my hoard of forgotten possessions and became something even better than they were before. I had experienced Recovery.

Now, we should consider that Tolkien only mentions things in his discussion of Recovery—probably because he was thinking about world building—but I think he’d agree that Recovery can apply to values as well.

In The Lord of the Rings, when we see Frodo’s sacrifice, Sam’s loyalty, Gandalf’s wisdom, Aragorn’s obedience to his destiny, and Legolas and Gimli’s friendship, we come alive to these values again. We really feel the sacrifice, the loyalty, the wisdom, the obedience, and the friendship, and when we see these values tested, we become alive again to what they are. The same can apply to negative values. We feel the fear of the Ringwraiths, we recoil with horror at what Sméagol has become, and we sense the hopelessness when Frodo refuses to destroy the One Ring.

This is an ultimate power of Fantasy (or Fairy Stories) that Tolkien is getting at. When an author isn’t constrained by the rules of our world, they are able to create one that changes how we see things and that makes parts of the real world seem even realer. And in that world, the Fantasy author can create a contrast, emphasize elements, or give new context, in a way that helps us to see how amazing the banal world really is. And in that, we realize that the world isn’t actually banal. We’ve merely lost the ability to see it as it is.

Thank you for reading past the dragon.

Be sure to check out Eric Falden’s Falden’s Forge to get the next installment of this discussion of “On Fairy Stories” by Tolkien.

I couldn’t find a good place to put this quote in my essay, but the whole topic of Recovery reminds me of this conversation between Eustace and Ramandu in C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952): “In our world,” said Eustace, “a star is a huge ball of flaming gas.” “Even in your world, my son, that is not what a star is, but only what it is made of.”

Doesn’t that quote give you chills? Anytime an author can add meaning and significance to the “normal” world and help me see it differently, I’m there for it. And this idea from Lewis raises so many questions and ideas. It’s practically a novel in itself.

So my question for you is this: Is there a Fantasy book you’ve read that helped you Recover a sense of awe for something you’d become inured to? I’d love to hear about it. (And I may add it to my every growing ThriftBooks wishlist.)

Without using the actual word “demystification.”

My two-year-old provided the inspiration for this example.

I recently tried to recapture this by challenging my best friend and myself to walk across Las Vegas from South to North in one go. It was a true adventure and a thousand times more enriching and fulfilling than making the drive or any single day of roadtripping I’ve ever had.

A sword wielded by Sigurd to kill the dragon Fafnir.

I think he thought Dickens’s use was too simplistic, but I think if he spent more time reading and thinking about Chesterton’s use of Mooreeffoc, he would have found a kindred spirit.

The man was effusive and rhapsodic.

And, yes, I was playing with foam swords at sixteen. I organized the neighbor kids into opposing armies and marched them at each other. I took a few out myself. Those were good times. And if you don’t like it, challenge me to a duel, and we’ll see who comes out without very minor bruising.

Thank you. I think you have finally made me understand why people are so attracted to worldbuilding as an art in itself. The world has gone grey for them, and they look to Oz transform it back into technicolor.

The thing is, I don't experience the world like this. It doesn't go grey for me. I have, if anything, the opposite problem. The world is too loud and too bright. I need to turn it down, not turn it up. And I think this was something I felt about LOTR from the beginning, even when I was a bigger fan than I am now, that everything was too big and too loud, as if real mountains weren't high enough and real rivers weren't fast enough. Qua worlds, I much preferred the miniature scale of Narnia. And this may explain why I have no taste for most modern fantasy. It is trying to turn up the volume on the world while I want to turn it down.

Perhaps this explains my affection for Robert Louis Stevenson, who famously said, “The world is so full of a number of things, / I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings.” No creeping disenchantment there.

This also makes me wonder if the angst over disenchantment that is so prevalent in Catholic literary circles today, and which is taken to be a fundamentally religious issue, is in fact simply a matter of personality, a matter of the mind for which the world quickly grows grey and quiet as opposed to a mind (like mine) for which it is always too loud and too bright.

This also highlights another thing that has always annoyed me about both Lewis and Tolkien. They are both living in the mid-century middle class bubble that saw life as the idyll of the Oxford don who had the summers free to go on walking tours across the English countryside. Tolkien, in the Shire, and Lewis in Narnia, present worlds in which everyone lives lives of respectable middle class comfort with lots of good food and tea and wine and tobacco. No such places ever existed. The poor (as Dickens well knew) lived no such lives, either in his England or in theirs. They are sentimental for a time when life was organized for the class from which Oxford dons were drawn, and for the life of gentlemen of leisure. Unlike Waugh, who also came from and wrote about that class, they are uncritical of them and see nothing of the work of others that sustains that lifestyle and makes it possible.

As the grandson of a coal miner on one side and of a teamster on the other (literally, my paternal grandfather delivered coal and moved furniture with a horse and cart) I'm honestly not long on sympathy for an Oxford don spending his long break on walking tours and feeling that the mountains are not as high as he would like nor the sky as blue.

Curiously, though, I think this may also have given me an insight into the Contemplative Realism movement, which on the surface seems the exact opposite of the fantasy world. But there too we find the same sense of impaired vision, or a desire to see more intensely. The literary prescription may be the exactly opposite, but the underlying aesthetic complaint seems to be just the same.

This is fascinating. Thank you.

I wonder if, in addition to the technique you describe, something else can Recover and re-mystify the world. If what you’ve described requires seeing the person, place, or thing in a renewed way, gratitude helps us see the whole context that way. Ingratitude and demystification seem to go together. The givenness of things draws our eyes to the Giver, which is ultimately re-mystifying but not for its own sake. Rather it re-mystifies for worship and for love.

What does this mean for reading and writing stories? Maybe this sense of gratitude shines through as one writes with a sense of wonder, rather than a sense of factory-worker control.