The 8 Eras of Fantasy Literature: A Short History of Magical Subversion and Rebellious Storytelling

Analysis and categorization of the fantastical from 2100 BC to 2024 AD

I came alive in grad school when I studied G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown detective stories and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise because both authors wrote stories that deal in ideas. Father Brown is an empathic detective who refutes the purely rational basis of Sherlock Holmes’s approach with psychology, spirituality, and intuition. This Side of Paradise is a refutation of Modernity—an absolutes-denying Postmodern work fifty years early!

In Literary Theory class, I learned literature could be split into eras (like Modern or Postmodern) based on themes, reactions, and ideas. I felt like an arborist studying the history of human thought by looking at the rings of trees. Only these trees had been processed into paper, bound into books, and laden with the most important things that Grad School Cliff could think of1: Ideas. (Pun intended.)

I was ecstatic learning about Mark Twain’s anti-Romantic satire in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the limp hand off from Modernism to Postmodernism after World War II, the New Sincerity’s efforts (a la David Foster Wallace) to stymie Postmodernism, and how Utopian literature shifted to Dystopian literature in the late 1900’s.2

Academic research and close reading felt like watching a tennis match where a never ending roster of players swapped out between hits.3

I loved it so much.

I’ve been studying the true differences between Science Fiction and Fantasy, so that old fire has kindled once more, and I’ve begun to ask, “Are there eras to Fantasy literature too? Do they change with general literature eras? Do they conform or are they antagonistic to mainstream trends? And what do they mean for me as a Fantasy writer/reader today?”

I began researching these questions but found that Fantasy literature hadn’t been formally sorted into eras (anywhere that I could find), and I decided to try it myself. This analysis is now complete and presented below. And while I learned a lot, I believe the greatest benefit to me was understanding the raison d’etre of Fantasy literature and how it is almost always a reaction against Realism and a subversion of mainstream trends. As a result, this research has matured my love of Fantasy and helped me to clarify my own writing and reading goals.

I hope that reading this analysis will do the same for you and that you’ll finish this essay with a better understanding of the eras of Fantasy literature, an appreciation for the progress and power of our beautiful genre, and an enthusiasm for joining the conversation. If you can make it through this essay, I’ll believe you’ll enjoy reading and writing Fantasy even more.

General Literary Eras

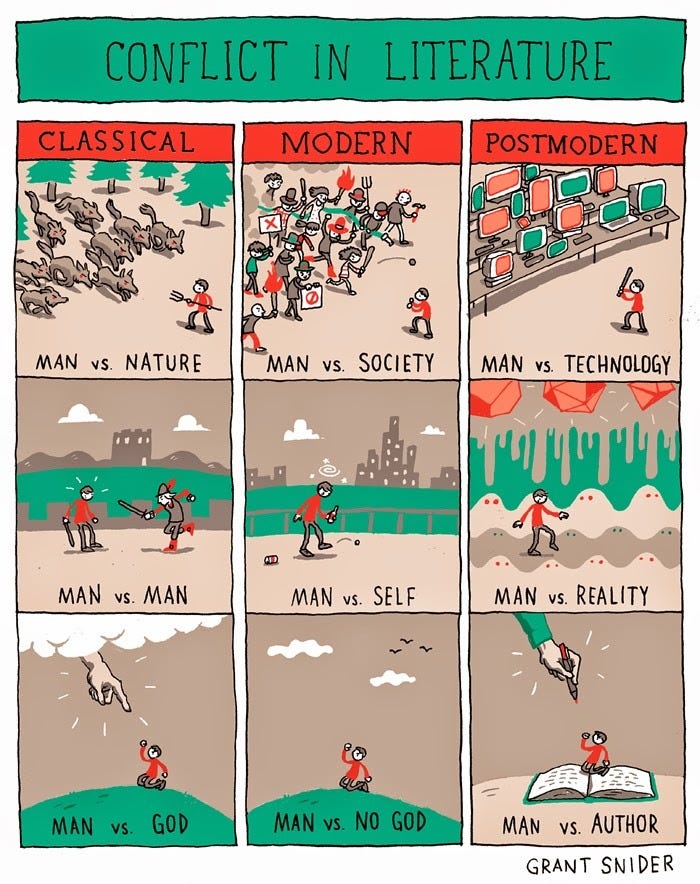

Before we dive into Fantasy eras, let’s establish a frame of reference by reviewing recognized literary eras. Doing so will help us to understand how Fantasy interacts with mainstream literature.4

Classical Literature (2000 BC - 500 AD)

This group includes Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Aesop, and Sophocles from Greece and Ovid, Horace, and Virgil from Rome. We also have early Christian writers like Saint Augustine, Tertullian, and Saint Jerome. These authors with their varied perspectives and theories of philosophy created a bedrock for Western Civilization but are hard to categorize under a single theme. Perhaps most important is a seeming shared belief in the possibility of progress.

Medieval Literature (500 - 1500 AD)

This era brought us Beowulf (~800 AD), The Song of Roland (~1050 AD), and tales of the court of King Arthur. The author most remembered may be Geoffrey Chaucer and his Canterbury Tales (1387-1400 AD) or Dante’s Divine Comedy (1321). Much of the lasting literature of this era would be philosophical, religious, and political—not fictional. According to The Norton Anthology, this era in Europe was hardly uniform but usually showed a preference for the Christian faith, had early experiments with self government, and elevated the idea of Chivalry as a code of conduct. Renaissance thinkers referred to it as “The Middle Ages” because they saw it as “a culturally empty time that separated the Renaissance from the Classical past.”

Renaissance/Reformation Literature (1500 - 1700 AD)

Fueled by a rediscovery of the Classics and ancient literature, the Renaissance in southern Europe pioneered Humanism, a philosophy that celebrates human achievement. In northern Europe, the Protestant Reformation, led by scholars like Martin Luther and John Calvin, questioned the Catholic church and championed a direct reading of Scripture over extra-Scriptural Catholic tradition. Both movements focused on rediscovering what had been lost (or little known) for a thousand years—a return to old truth. From this era, we remember creative authors like Miguel de Cervantes, Francois Rabelais, Erasmus, Edmund Spenser, Philip Sidney, John Milton, and William Shakespeare.

Enlightenment Literature (1700 - 1800 AD)

Where the Renaissance had championed the supposed inherent glory of humanity itself and the Reformation had championed the Bible over the Pope, the Enlightenment responded with a Deistic emphasis on rationalism and science. Enlightenment writers made important leaps in political theory, science, and philosophy. Important fictional books of this era included Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), but most “top ten books lists” of the Enlightenment would be exclusively non-fictional.

Romanticism/Transcendentalism (1800 - 1870 AD)

Having had enough of an “Enlightenment” that birthed burdensome Existentialism and failed politically in the French Revolution, British authors embraced Romanticism. This movement focused on nature and the individual’s emotions (as opposed to strict logical argument). America’s Transcendentalist movement mirrored Romanticism but with an emphasis on the individual’s ability to succeed on their own without the help of others or technology. Prominent authors included Wordsworth, Coleridge, Blake, Keats, Shelley, Lord Byron, Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. This was also when France provided us authors like Alexander Dumas and Victor Hugo.

British Realism/Victorian Literature (1837 - 1901 AD)

Victorian Era literature in Great Britain often reacted against the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) born of the scientific advancements brought on by the Enlightenment. Authors and society at large were concerned about the fast moving changes caused by technology, and they responded by focusing on the individual and morality and by invoking sentimentality or aesthetics (things industrial machines have no ability to compete with). And, unlike the Romantics, they wanted to acknowledge the bad parts of society, so they often focused on the urban over the rural. They brought to bear a strong sense of morality and wrote extensively about class struggles. Popular authors include the Bronte sisters, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Elizabeth Browning, George Eliot, Rudyard Kipling, and Charles Dickens.

By the end of the century, a few authors like Oscar Wilde wittily revolted into Aestheticism and Existentialism and tended to create “art for art’s sake,” tired of literature that seemed to bend itself around a message or moral. Edwardian authors like G. K. Chesterton then (equally wittily) argued back for the beauty of meaningfulness and order over chaos—a short-lived movement before Modernism.

American Realism/Naturalism (1865-1910 AD)

During the British Victorian era, the Civil War caused many American authors to reject Romanticism and Transcendentalism. They turned to Realism, which harshly rejected the previous era’s idealism. The flagship example is Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which ridicules the tropes and “rose colored glasses” wearing that came before. The Realist attitude seems to be one of “Yes, things can be good, but they don’t start that way. We have a long way to go, and it will be hard.” And like their Victorian cousins, they wrote about the commonplace with a great level of detail (think Emily Dickinson).

As the popularity of On the Origin Species grew and as Americans turned their attention to the vast, hostile landscapes to their west, Realism birthed the similar but harsher Naturalism. Naturalists emphasized nature—what else?—and accepted a more deterministic outlook on life, one that was often bleak and brutal. Think “To Build a Fire” by Jack London where the main character dies because he cannot start a fire on a cold Yukon day. Other influential Realists and Naturalists included Theodore Dreiser, Edith Wharton, Henry James, and Stephen Crane.

Modernism (1910-1953 AD)

On both sides of the Atlantic, Modernism brought disillusionment into vogue. While the era began optimistically with technological advances and a belief in man’s destiny to (more or less) defeat nature, World War I shattered that hope, showing mankind that their greatest opponent was actually themselves.5 Then the post-war boom spawned the opulent Jazz era in which Western civilization seemingly tried to forget the problems highlighted by World War I, which H. G. Wells had mistakenly called “the war to end all wars.” This proved optimistic because society was once again confronted with painful truths in the Great Depression, the second World War, and the horrors of the atom bomb—a “pinnacle of human invention” that killed 200,000 people in a few minutes.

Through all this, Modern authors like T. S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, W. H. Auden, and others grappled with the disappointment and confusion of a human race that had failed its utopian goals. In 1953, Samuel Beckett premiered his play Waiting for Godot that encapsulates the spirit of the Modern era: so much had been promised, but Western Civilization was still waiting. Thus, Modern literature, at its core, is a mourning of the failure of human progress.

Postmodernism (1945 AD - Present)

Realism had promised human advancement through technology and science, and Modernism had mourned that failure. When Postmodernism appeared after World War II, its proponents advocated for a deconstruction of society’s presuppositions since apparently those had all been wrong and had only gotten us into trouble. Postmoderns favored subjective and personal experiences over absolute truths held by previous eras. They believed that the society created by the Moderns was unfair to minorities and women. And they distrusted power structures and social hierarchies (especially inherited ones)—these were the people who got us into trouble in the past, right?

Postmodern authors embrace the absurd and ironic, and their books are often metatextual and tend to complicate literary conventions (think of the whirlwind experience of reading a Kurt Vonnegut book). They play with language and highlight the difficulty of achieving meaning in language, which they acknowledge as a subjective tool. Postmodern authors deconstruct reality and laugh at precepts (absolute truth, science, religion, progress, social power structures, etc.) that have been esteemed since the Enlightenment. Creative postmodern authors include Joseph Heller, Allen Ginsberg, Truman Capote, Thomas Pynchon, Toni Morrison, and others.

The Pendulum Swings

The important thing to learn from this brief exploration of general literary eras is the vacillation between absolutes. Eras swap between prioritizing the internal or the external, the individual or the community, rationality or emotion, optimism or pessimism, the natural or the manmade, progress or the past, objectivity or subjectivity, etc.

For an example, let’s just look at whether different eras prioritized the past or the future:

The Ancients and Medievalists looked to building the future.

The Renaissance/Reformation looked to rediscovering truth from the past.

The Enlightenment chased progress into the future.

The Romantics/Transcendentalists romanticized the happy past.

The Victorians/Realists/Naturalists reformed society for the future.

The Moderns mourned the failures of the past

The Postmoderns seem to tire of the rollercoaster and to ask to be let off with all their bluster about rejecting absolutes and subjective morality, but even they are deconstructing the past and present so as to focus on improving the future.

As Solomon says, “What has been is what will be, / and what has been done is what will be done, / and there is nothing new under the sun.”

Studying mainstream literary eras reads like the story of humankind. It’s a beautiful, tragic, intriguing, and recursive story, but it is our story, and understanding it helps us to be better readers and writers.

Fantasy Literary Eras

And understanding the eras of Fantasy literature is just as important because it’s the history of human imagination—something that unites us across the millennia. Plumbing these depths—the mystical, the supernatural, the impossible things we dream about, the questions we speculate—will give us an even fuller picture of what humanity is.

Unfortunately, Fantasy literary eras do not follow the same timelines as general literature and are hard to determine for a few reasons:

Fantasy wasn’t a widely recognized genre until the 1950s.

Fantasy contains many different sub-genres.

Being a single genre, Fantasy trends are more susceptible to the influence of a single author (like Tolkien, Lewis, Stephanie Meyer, or George MacDonald) who might shape the genre for decades to come.

Fantasy has a natural escapist bent, and its more populist authors are often less concerned with the dealings of the real world.

Most importantly, Fantasy literature is often a reaction against the prevailing themes of the time.

Keeping these in mind, let’s proceed with humility and a willingness to accept generalities if in doubt. I’ve anchored my analysis in the work done by Farah Mendlesohn and Edward James (heretofore M & J) in their archival A Short History of Fantasy (2009) as well as many other resources. And I believe that with these approaches, the eras of Fantasy are possible to organize.

Progenitor Fantasy (2100 BC - 1100 AD)

This era includes ancient epics, legends, and mythological belief systems (see: Fantasy worlds) from many cultures; most important to Western Fantasy were Greek, Roman, Norse, German, and Celtic. And after The Epic of Gilgamesh (~2100-1300 BC) (the first recorded Fantasy story), the most important to Western tradition have been Homer’s The Odyssey and The Iliad (~750 BC) and the Old English Beowulf (~800 AD).

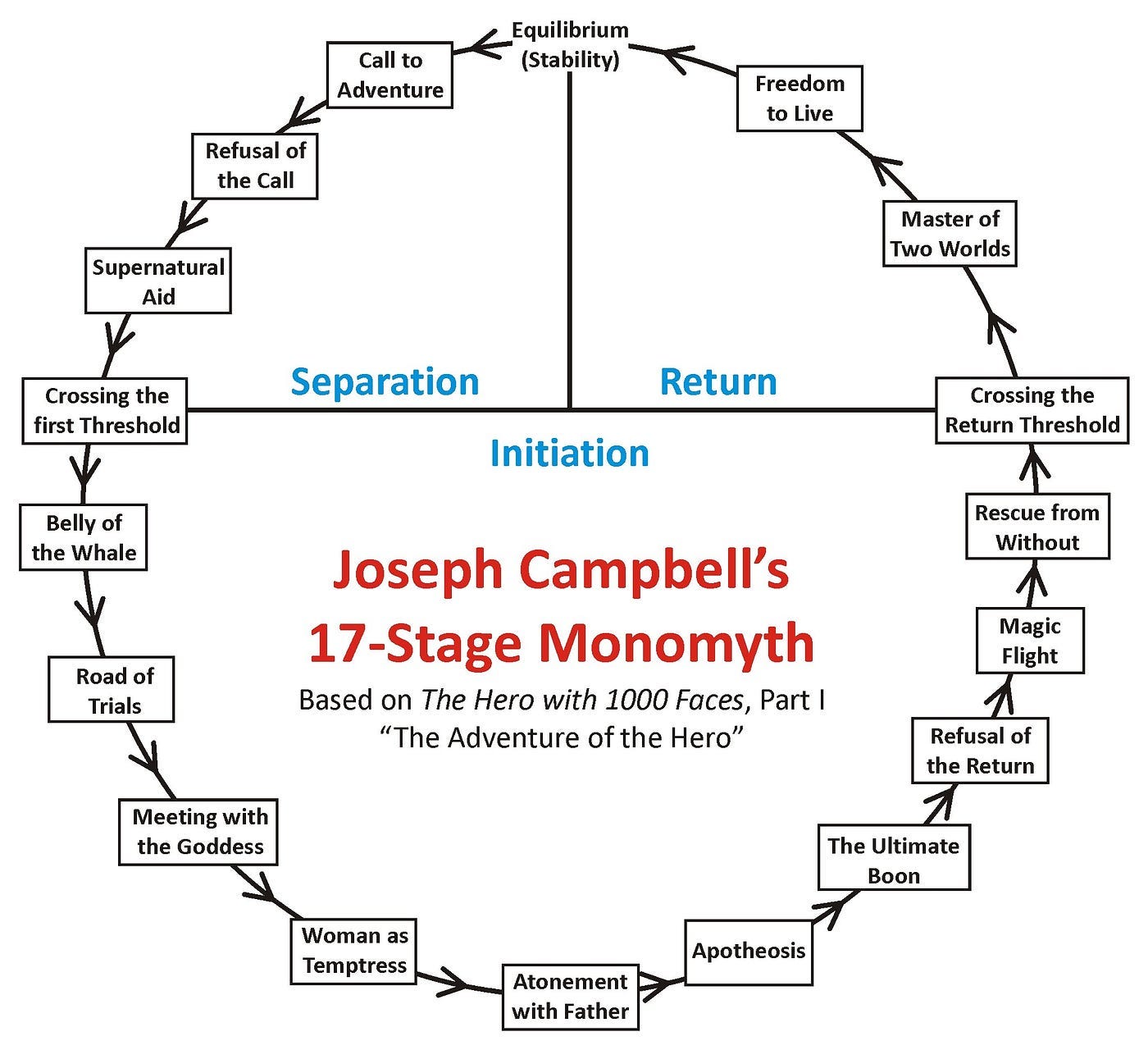

While there are others, these four stories alone are enough to account for characteristics that would exist in Fantasy literature until the present day: epic quests, heroic battles, monsters, magic, moral trials, superhuman warriors, and (most importantly) the return home. In all this, we have the blueprints of one of humankind’s most sacred stories: the hero’s journey as laid out in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. It’s the story of the call to adventure, trials, growth, and returning as a changed person, and it’s the oldest and most important legacy of the Fantasy genre.

Preconstruction Fantasy (1100 - 1760 AD)

The Preconstruction Fantasy Era bore troves of influential Fantasy material that will likely inspire writers as long as Fantasy is a genre. This happened through (1) translation and compilation of mythologies, (2) the Medieval Romance, and (3) early story form experimentation.

Arguably the most influential of the three was the Western gathering of various cultures’ fantastical stories. This included Antoine Galland’s translation of the Arabian The Thousand and One Nights (1704), the Renaissance’s rediscovery and celebration of ancient Greek texts, the translation of Nordic mythologies, early translations of the Icelandic sagas, and a strong interest in Celtic/Welsh stories and folklore. Celtic mythology in particular impacted future generations with their concept of Faerie as a magical land parallel to ours where the capricious and powerful fey (see: fairies) live (M & J).6

A keystone genre of the time was the Medieval Romance. In this case, “Romance” doesn’t have the modern meaning but rather refers to knightly adventure, chivalry, and courtly interactions. One such is Histories of the Kings of Britain (1136) by Geoffrey of Monmouth, which codified or invented many early Arthurian stories and elements including the wizard Merlin. Another is Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), which ensured Arthurian legends would be read for hundreds more years. Also notable is Edmund Spenser’s epic poem The Faerie Queen (1590-1596), which combined Arthurian legend with Greek gods and Faerie.7

Finally, from the 1600s to the mid-1700s, this era gives us many early experimentations with the use of the fantastical by popular Renaissance and Enlightenment era authors. Most notable are several plays by Shakespeare (including A Midsummer Night’s Dream), John Bunyan’s allegorical The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726).

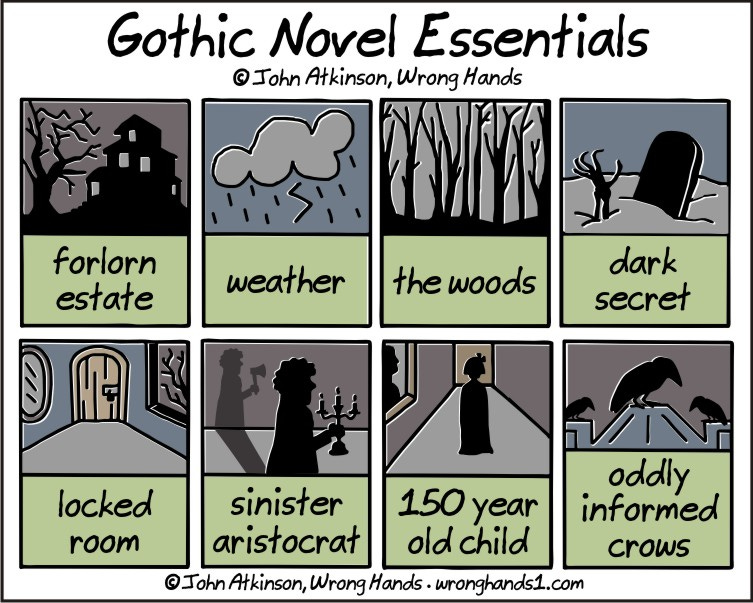

The Gothic Era (1760-1830 AD)

While the Enlightenment featured some notable Fantasy stories, the era as a whole emphasized Rationalism and Empiricism; the effect of much of the scientific advancements of the era was actually to dispel myths about how the world worked, not to imagine more. Thus 1700-1800 were less friendly to fantastical elements in stories. And as noted before, the pendulum always swings, so authors and readers responded with the Gothic novel.

M & J write that “the very idea of a world that could be controlled and understood was subverted into a mode of literature, the Gothic, in which this surface world is a delusion.” While Enlightenment thinkers eliminated mystery, Gothic writers showed readers that within every ruin, behind every locked door, in every mysterious attic, there could lurk a mystery or a hidden evil. Gothic writers sought to re-mystify an enlightened world.

Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) was the first Gothic novel, and it included once great structures fallen into decay, a fascination with the Medieval, an eerie atmosphere, and a tense and slow buildup to a mysterious reveal of something that may or may not be dangerously fantastical. If in reading a Gothic novel, you find yourself asking, “Is there anything actually dangerously supernatural going on here?” you’re right where the author wants you (even if the eventual answer is “No”). Other popular Gothic stories include Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839), and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847).8

The Era of Faerie (1840-1900)

M & J write, “Arguably . . . fantasy as a genre only emerges in response (and contemporaneous to) the emergence of mimesis (or realism) as a genre.”9 And while British and American Realism spawned as counters to Romanticism in the mid 1800s, British faerie stories seemed to spawn as a quick response to Realism.

Realists might see the preference for fantastical creatures or other worlds as a form of escapism, but this era’s actual goal is to recapture a sense of awe. Where the Gothics found it in mystery and the Romantics found it in the sublime, Faerie Story authors found it in their imaginings of the extra-natural.

And this was expressed in many ways:

Faerie Story Fantasy (perhaps first and foremost) included a revival of the Fairy Tale. The Brothers Grimm had already released their 1812 collection of German fairy tales. They might be fairly called Romantics, but their dark collection also seems to bridge a gap between the Gothic and the Faerie Story. After them came Hans Christian Anderson who wrote his own fairy tales. The last great fairy tale collector was Andrew Lang who published eleven collections from 1889-1910, the first being The Blue Fairy Book. These four authors ensured the popularity of the fairy tale and laid the bedrock for the coming Fantasy genre. Unfortunately, serious and socially focused Victorian sensibility tended to categorize fairy tales as children’s literature, but as we’ll see, the children readers of this era would be the adult Fantasy writers of the next.

The Faerie Story era also gives us the first Fantasy novels (even if all Fantasy back then was referred to as “Faerie Stories”). Sara Coleridge wrote Phantasmion: A Fairy Tale (1839), the first Fantasy novel, which inspired the grandfather of the Fantasy genre, George MacDonald. His first novel was Phantastes (1858), about one man’s dangerous journey into Faerie. He also wrote At the Back of the North Wind (1871), The Princess and Goblin (1872), The Princess and the Curdie (1883), and Lilith (1895). His stories combined a Christian sensibility with the fantastical, and he rebelled against the Victorian idea that faerie stories were only for children. He once said, “I do not write for children, but for the childlike, whether of five, or fifty, or seventy-five.” Essentially, he showed future authors that Fantasy could be novelized and could be written for adults, and both Tolkien and Lewis cited him as a direct inspiration. M & J even note that his “terrifying goblins” are “the direct ancestors of Tolkien’s orcs.”

MacDonald was a friend of Lewis Carroll and encouraged him to lengthen and publish Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). Carroll reacted against concrete Realism and explored the absurd and the surreal. He engaged in what M & J call “whimsy,” described as “fancy, and the slightly surreal, with a sense of randomness that can be both delightful but also unnerving.” Carroll’s style of writing with its puns and anti-math and anti-logic, I think, captures the spirit of the fae—playful, magical, capricious, and dangerous.

The final author of this era I’ll mention is William Morris who wrote the first Fantasy novel set in a world entirely disconnected from ours. Where MacDonald’s narrator in Phantastes had gone wandering into a Faerie wood from our world, Morris’s Ralph in The Well at the World’s End exists in another reality, which makes this the first High Fantasy novel. Morris is also known for translating the Icelandic sagas, writing in strongly Medieval settings, using an archaic pseudo-Medieval diction in his writing, and being a Pre-Raphaelite. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (started in 1848) was a collection of artists and creatives who idolized Medieval art styles. Their interest in knights and chivalry, and their eye-catching, colorful paintings, often of Feudal subject matter, reawakened interest in the Middle Ages, which precipitated the inception of Fantasy as a genre.10

Faced with the negatives of industrialization and modernization, Fantasy authors of this period seemed to be asking, “Is this as good as it can get?” They advocated a return to their cultures’ roots, to imagination, and to Faerie.

Anti-Modern Fantasy (1900-1948)

If we hold to M & J’s theory that Fantasy is inherently a reaction against Realism and the “serious,” “real” endeavors of an age, let’s consider the chief events of the early 20th century:

Humans used technology to wage war against nature (for instance, air conditioning was invented in 1902). But as a result, we seem to have perfected the art of pollution, and Americans had to create the National Park Service to protect nature from themselves.

We believed World War I (with all its technologically fueled atrocities against humans) to be “the war to end all wars” until we arrived at World War II and the Atom Bomb was dropped.

The economic prosperity of the Roaring 20’s (brought on by wartime industrialism) nosedived into The Great Depression.

Modern medicine couldn’t save Americans from the Spanish Flu I, which (by some estimates) may have been the most deadly pandemic in human history with 50 million killed.

Even the Titanic, the ship that “not even God himself could sink,” ran into an iceberg and sunk on its maiden voyage.

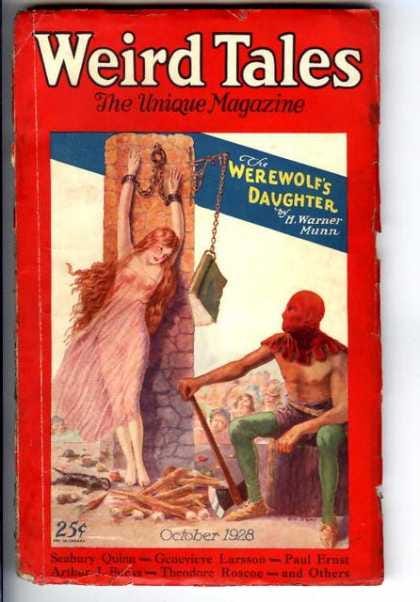

And while mainstream American authors fled to France to write existential tragedies, the Fantasy genre began a slow and serious conquest of Western imagination in a multi-pronged attack. (Note, according to M & J, this time period also includes the first time “Fantasy” was used as the title of the genre.)

First, Moderns needed an escape from reality (and maybe from Modern authors), and Fantasy was willing to provide this. Maybe people needed to believe that magic could still happen and that happy endings were possible. While other authors despaired, Fantasy authors were often more hopeful and optimistic (ignore the Horror Fantasy of H. P. Lovecraft). If they couldn’t find hope or progress or heroism in the real world, they imagined it in another.

Second, this was a golden age for Fantasy children’s literature. Many of these stories are still popular and part of Western culture today. We have L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), Edith Nesbit’s Five Children and It (1902), Kenneth Graham’s The Wind in the Willows (1908), J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan and Wendy (1911), A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), and E. B. White’s Stuart Little (1945). These stories were fantastical, often light-hearted, and almost always full of happy endings.

Third, in America, the primary medium for adult Fantasy was magazines or “the pulps.” And it’s with these publications like Weird Tales (the most iconic) that we see a surge of general interest in Fantasy. For a while Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Horror were published together, but during this time period, they differentiated, authors started to specialize, and publications focused on a single genre of the fantastical. Science Fiction was the first to separate (as it was the most successful of the three in this time period), butt eventually H. P. Lovecraft spawned a new and separate horror genre with his “The Call of Cthulhu” (1928) and other eerie tails “typified by a morbid belief in something terrifying beyond” (M & J). Meanwhile, American Fantasy took more life of its own with the introduction of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian first published in Weird Tales in 1925. To describe this type of story, Fritz Leiber coined the phrase “Sword-and-Sorcery” in 1939, and it was this genre with its magic, other worlds, Medievalism, episodic quests, and morally ambiguous situations that defined popular Fantasy before 1949.

Unfortunately, much pulp Fantasy was sensationalist and mere escapism, and this era’s American Adult Fantasy provided only a few lasting names. As Ursula K. Le Guin (who grew up in this time) points out in the retrospective “Escape Routes” (1974-75), literary escape can be to a richer, deeper world or to a thinner, faker world. And according to her essays in The Language of the Night: Essays on Writing, Science Fiction, and Fantasy (collected in 1979), she thought most pulp fiction escaped to the latter. She felt (and seems to be correct) that most pulp authors delivered up imaginative but empty ideas that lacked “moral significance.”

Finally, while Americans had the Pulps, Great Britain provided us with several noteworthy Fantasy novels, many of which influenced Tolkien or Lewis or both in the creation of their fiction. David Lindsay published the space exploration Fantasy A Voyage to Arcturus in 1920. E. R. Eddison wrote The Worm Ourborous in 1922; it’s a Medieval and Norse-infused High Fantasy. Lord Dunsany released the hugely influential High Fantasy The King of Elfland’s Daughter in 1924. In 1926, Hope Mirrlees released Lud-in-the-Mist, which took inspiration from Christina Rossetti’s long poem “Goblin Market” (1862). And finally from 1938-1940, T. H. White published portions of what would eventually become The Once and Future King (1958)—an epic, sometimes comic, sometimes somber reflection on the reign of King Arthur and the question of whether “might makes right.”

The Hinge Decade (1950-1958)

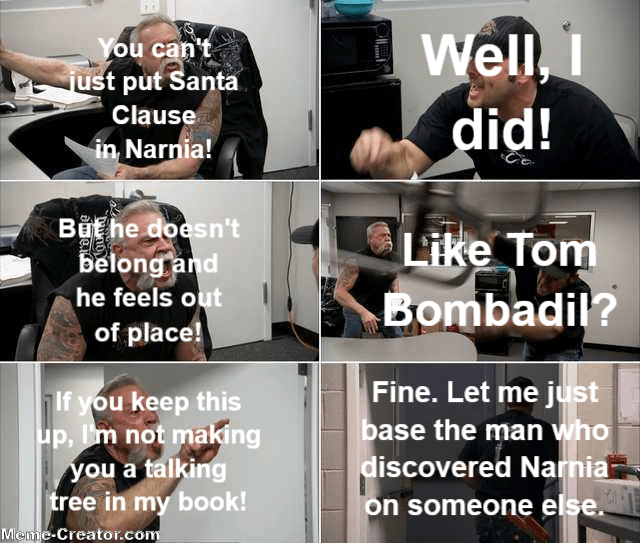

I’d like to posit that three authors provided an end cap to the Anti-Modern fantasists and that (arguably) each perfected the modern version of a single Fantasy sub-genre redefining the future of Fantasy. With The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955), J. R. R. Tolkien created the most holistic Fantasy world to that point and wrote the genre’s most influential Epic Fantasy by drawing on themes from Modernity, myth, and late 1800s conceptions of Faerie. C. S. Lewis, a Medieval scholar, combined Medieval thought with his Christian faith and a smattering of different mythologies to create the most important Fantasy children’s series of all time, The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956). And T. H. White provided us what may be the greatest adaptation of Arthurian legend that will ever be written, the standard for future Comic Fantasy, and perhaps the highest quality Fantasy social commentary ever—all in one book: The Once and Future King (1958).

Tolkien had already written a wonderful children’s story in The Hobbit (1937), but readers clamored for a sequel, and he delivered The Lord of the Rings in the 50s. Much has been said about this series, and it stands as the single greatest Fantasy writing achievement of all time (most would agree). Its influence is present today to the point where most High Fantasy worlds feel like riffs on Middle-Earth. Tolkien essentially codified elements of the Epic Fantasy that all future writers would be forced to either adhere to or react against. It will be a long time before a High Fantasy story can escape being compared to Tolkien’s work. Key influential features of The Lord of the Rings include Middle-Earth’s races, a powerful and magical weapon, an epic battle between good and evil, Medievalism, an invented language, evil monsters, a dark lord, multiple storylines, travel through dangerous landscapes, etc. While Tolkien invented none of these concepts, he brought them together and did them better (and more thoroughly) than anyone had before. Then, the immense popularity of The Lord of the Rings cemented these elements as features of the Epic and High Fantasy sub-genres.

But more important were the themes of The Lord of the Rings. There are many, but much of the series can be read as a Catholic response to the two World Wars, the anti-natural nature of Modern industrial technology, and man’s desire for power. Tolkien seems to have seen Frodo and Sam as stand-ins for the young British men sent off to fight in World War I. And while Tolkien denied direct allegory to actual history, many read the One Ring as a metaphor for the weapons of mass destruction created at this time such as chemical weapons and the Atom Bomb. The anti-Industrialism themes are clear throughout: the most notable ones are in “The Scouring of the Shire” chapter. After the Hobbit heroes return to the Shire and cleanse it of Saruman’s factories and machines, Sam uses an elven gift to replant and heal his home, setting everything back to the way it should have been. The Ring itself and every character who interacts with it show Tolkien’s thoughts on temptation and the corrupting nature of power.11 I think it’s Tolkien’s ability to so thoroughly create a fully engrossing world filled with wonder and adventure while dealing with topics important to its readers that makes The Lord of the Rings so special and that seals its place as the greatest and most influential work of Fantasy of all time.

C. S. Lewis wrote children’s literature with his seven book Portal Fantasy, The Chronicles of Narnia. The series mostly tells stories of children from our world being called to Narnia by the Christ-figure Aslan to go on important adventures or to save Narnia from invading witches and warlords. The series heavily features Christian allegory, Medieval lore, and Fantasy elements from a variety of mythologies. I believe Lewis was, in particular, inspired to write it as a Portal Fantasy by Celtic and Irish conceptions of Faerie as a parallel world and by George MacDonald’s Phantastes (an inspiration Lewis cited in his autobiography Surprised by Joy).

Where Tolkien wrote High Fantasy (a Fantasy world separate from ours), Lewis’s main legacy for the genre was to set a standard for Low Fantasy (a Fantasy world connected to ours). His stories had many readers seeing Narnia behind every piece of furniture and wishing their wardrobes would let them into that magical country. M & J also claim “that [Narnia] sets a pattern for future portal fantasies, in which the travelers from Earth are uniquely equipped to rescue another land from its travails.” I think this oversimplifies things a bit since Aslan is the one who does the equipping of the world-hopping children, but M & J are right about how it influenced other authors. Lewis also set the standard for Children’s Fantasy and helped prepare the way for Young Adult Fantasy with his books about children doing big, important things (think young Caspian commanding an entire army) that both children and adults could read and re-read while discovering something new every time. Beyond all these, Lewis also showed the potential of Fantasy as a genre for Christian authors and emphasized the whimsical side of Fantasy (something Tolkien certainly did not do) that would resurge later.

T. H. White is a contentious addition to the Tolkien and Lewis duo. While his influence doesn’t match theirs, his Arthurian adaptation The Once and Future King (revised and compiled in 1958) encapsulates the general Modern literary era perfectly. More than any other novel of the era, I think it bridges the gap between mainstream and Fantasy literature with its incisive social and political commentary. And, of course, it has had an important influence on the Comedic Fantasy and Satiric Fantasy sub genres. He was a predecessor to Terry Pratchett, and both Gaiman and Rowling cite his influence.

There are two sides to The Once and Future King. The first is Arthur’s light-hearted upbringing and tutelage by Merlyn who teaches him about government, morality, and human nature. The second is the darker, grimmer telling of Arthur’s reign when he makes difficult decisions and grapples between doing what’s right and imposing his will on others even when they wrong him grievously. The power of The Once and Future King is in how it tackles Modern questions in an Arthurian setting—universal questions of war, superior forms of government, social law, and handling disappointment. White reviews these so humbly and so carefully that it’s a wonderful experience to learn from him through his characters. The story is a clear commentary on the state of the world between and after the world wars and the philosophical question of how to make the world a better place without becoming a tyrant.

Together, Tolkien, Lewis, and White deliver the final words of Anti-Modern Fantasy and set the tone for the generation to come. They perfected their respective sub-genres, and none of them have been matched since. Their massive success prepared the way for the next generation of authors who they not only inspired but also proved to publishers could be extraordinarily popular.

Age of the Heroic Epic (1954-1999)

The most significant trend line of this time period was the growing interest in Heroic, Epic, and Quest Fantasies (heretofore conglomerated as Heroic Fantasy). And thus we have to acknowledge that Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings in particular is the father of this era. It created an appetite among readers for Heroic Fantasy, and it showed publishers the potential profit.

In the 50s, the genre was mostly quiet apart from Tolkien, Lewis, and White. We did receive The Martian Chronicles (1950) by Ray Bradbury, The Borrowers by Mary Norton (1952) I Am Legend (1954) by Richard Matheson, The Cat in the Hat (1957) by Dr. Seuss, and a few others, but as the popularity of The Lord of the Rings grew (albeit slowly at first), publishers began to understand this audience better.

So in the 60s, publishers became more open to Fantasy authors but still mostly published Children’s Fantasy. We gained Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth (1961), several children’s books by Roald Dahl, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time (1962), and most notably Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) (which would exert a strong influence on the Harry Potter series). On the adult side, we gained Michael Moorcock’s “The Dreaming City” (1961) the first Elric of Melnibone story, Anne McCaffrey’s influential Dragonflight (1968), Pete S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn (1968), and a few others. A big moment came in 1969 with the launch of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, which republished novels like The King of Elfland’s Daughter, The Wood beyond the World, and Phantastes. It resurrected many old classics, solidified a cannon, and helped establish the genre.

Maybe most impactful in the 60’s was that the paperback publication of The Lord of the Rings finally made it to America after many questions about import costs and copyright. When it appeared, it soared in popularity, took the series to new levels of popularity, and changed everything for the Fantasy genre . . .

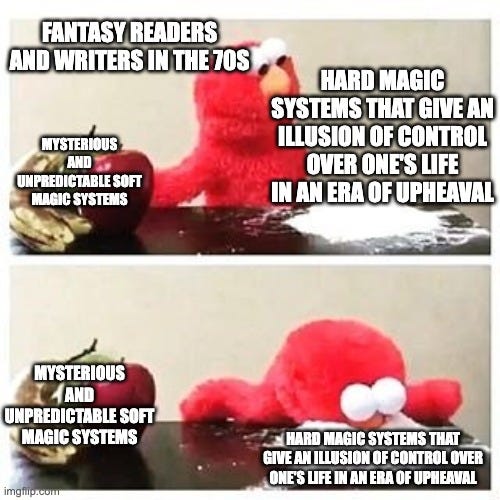

. . . so much so that in the 70s, the entire Fantasy genre exploded in popularity.12 Once readers tasted Tolkien, they wanted more quests, more Fantasy, and more supernatural. Many authors from the 60s (Le Guin, McCaffrey, Moorcock, etc.) were happy to oblige and doubled down on their series. But readers also gained hundreds of new Fantasy works including Diana Wynne Jones’s Wilkin’s Tooth (1973), Richard Adams’s Watership Down (1972), William Goldman’s The Princess Bride (1973), Gene Wolfe’s The Devil in a Forest (1976), Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire (1976), Stephen R. Donaldson’s Lord Foul’s Bane (1977), and the notorious Terry Brooks’s The Sword of Shannara (1977),13 which many hold to be a ripoff of The Lord of the Rings. We also have the supposed Science Fiction Star Wars: A New Hope being released in 1977 (which I argue is actually just Space Fantasy), and the first release of the Dungeons and Dragons roleplaying game system in 1974. While much Fantasy before 1950 had included magic, how the magic worked had been undefined and mysterious—what we’d call a soft magic system today (

explains magic systems further in a post of his I recommend). The point of soft magic is that we don’t know how it works. It’s enough that there is magic, and the lack of understanding contributes to the awe we and POV characters feel. But in the 70s in particular, authors started to favor hard magic systems that required explanation and were almost scientific in their reliability, and I have to believe that the release of Dungeons and Dragons (1974) with all its rules and organization did a lot to speed this trend along. I’m sure this trend towards hard magic systems says something about how out-of-control readers felt in that historical period.The 80s continued the upward trend of Fantasy popularity with even more notable books than the 70s. And even though the sub genre Sword-and-Sorcery had seen a small revival in the 60s and 70s with republication of the Conan the Barbarian stories, Heroic Fantasy with its larger scale battles and more world-defining storylines was the dominant Fantasy form in the 80s. The 80s brought us Gene Wolf’s The Shadow of the Torturer, Stephen King’s The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (1982), a couple of books by Joyce Carol Oates, James Blaylock’s The Elfin Ship (1982), Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon (1983), Guy Gavriel Kay’s The Fionavar Tapestry (1984-1986), Diana Wynn Jones’s Howl’s Moving Castle (1986), Bryan Jacques’s Redwall (1986), Stephen Lawhead’s Taliesin (1987), and quite a few books by Terry Pratchett. The most noteworthy fantasy author of the 80s, Terry Pratchett wrote Satirical Fantasy mostly in his made up Discworld. Many of his 41 novels lampoon society or the Fantasy genre itself.

We also see the rise of Magical Realism—a style characterized by magical elements intruding in to the real world but in which it is unclear just how magical the intrusion is—which I believe to be a clue that in the midst of the Cold War readers were desperate for a little magical infusion into their lives. These books would have been Low Fantasy and a slight return to older Fantasy in which Faerie trespassed on the real world.

Finally, we have the 90s. As M & J point out, during this time “Medievalist fantasy became really big business,” and long epic series full of thick books became the norm. The best example of this may be Robert Jordan and his seemingly unending The Wheel of Time series (1990-2013), which was finished by Brandon Sanderson after Jordan died in 2007. Other important works from this decade included Good Omens (1990) by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett, Gaiman’s Neverwhere (1996) and Stardust (1999), Andrzej Sapkowski’s The Witcher series (1990-2013), Terry Goodkind’s Sword of Truth series (1994-2015), Phillip Pullman’s anti-Lewisian His Dark Materials trilogy (1995-2000), Robin Hobb’s Farseer trilogy (1995-1997), George R. R. Martin’s Grimdark series A Song of Fire and Ice (1996-present), the beginnings of Daniel Handler’s A Series of Unfortunate Events (1999), and many books by the inexorable and indefatigable Terry Pratchett (16 novels in the 90s alone besides Good Omens!), not to mention other authors from the last two decades who continued publishing. And, of course, J. K. Rowling must be acknowledged, but while she did publish three Harry Potter books in the 1990s, I believe her impact is better saved for the next era.

Overall, Heroic Fantasy was central to the Fantasy genre during this time period, but it could only be a phenomenon if its underlying themes resonated with the culture at large. And I think the reason this genre resonated so well with audiences during this period was the vacuum left by Postmodernity. When philosophers and mainstream art deny truth and absolutes and power structures and meaning, us normal people are left with a gap to fill. We want life to mean something, and I believe that for many readers Heroic Fantasy provided that. These stories had heroes with clear senses of right and wrong (even if they didn’t always do what was right) on a quest to do a thing to accomplish an objective for a reason—what could be more definite and anti-Postmodern? In these stories, there’s an obvious right thing to do, and often someone admirable is doing it. In the midst of the Vietnam War, the Cold War, stock market crashes, recessions, energy crises, Watergate, and dozens of other crises and scandals, Heroic Fantasy seems to have been popular because it gave readers a world where things made sense.

Of course, many of the heroes of the Age of Heroic Fantasy were anti-heroes: Han Solo, Elric of Melnibone, Paul Atreides, and Geralt of Rivia to name a few. Anti-heroes are people who don’t look like heroes but who must save the day. They featured heavily in the Age of the Heroic Epic—a classic Postmodern questioning of established metanarratives—and seem to suggest that this age was more than an ode to heroism: it was a debate about what a hero is. The authors and readers of this time period don’t seem to have come to a conclusion, but the important thing is that they wanted a hero. In a world without heroes, Fantasy literature was a comforting and optimistic counter-cultural phenomenon.

The Fantasy Diaspora (2001-Present)

By nature of you and I being in this era right now, we don’t really know what’s going on, and we won’t until something new comes along and reacts against it.

But . . . I do have a theory.

I think that since 2001, we have been living in what I call the Fantasy Diaspora. Not only has Fantasy grown in popularity, but it has multiplied in style and type, and it has spread everywhere. I’ll explain how with five points:

J. K. Rowling started an avalanche of Young Adult Fantasy. She published the Harry Potter series from 1997 to 2007, and it’s now the highest selling book series of all time. While she contributes little in terms of new ideas or forms to the Fantasy genre (many of her ideas are heavily inspired by others), just as Tolkien did for Epic Fantasy, she showed publishers how profitable Young Adult Fantasy could be. Instantly the market responded with stories like Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games series (2008-2010) (technically sci-fi), Stephanie Meyers’s The Twilight Saga (2005-2008), Christopher Paolini’s Inheritance Cycle (2002-2011), Erin Hunter’s Warriors series (2003-present), and dozens and dozens of others. A common Harry Potter trend in many of these is of a seemingly insignificant child being told they are actually someone very special.

Harry Potter was first read by Millennials (1981-1996), a generation known for being raised with the belief that “you can be anything you want.” This was fertile soil for Fantasy literature, not because Millennials would start studying magic,14 but because they were more likely to identify with the heroes of the stories and to want heroes that looked like themselves. In the few decades before 2001, Fantasy was the domain of children and a “nerd culture” populated mostly by white males. But in the 2000s, other demographics became more interested in Fantasy, and there was a cry for representation in Fantasy stories for women and for racial, LGBTQ+, and geographic minorities. And this in turn led many minority authors to take part in the Fantasy tradition, notably including N. K. Jemisin, T. J. Klune, and Ken Liu.

The first Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings films were released in 2001 bringing peak Fantasy stories to mainstream audiences who otherwise cared little for Fantasy and who hadn’t (and likely still wouldn’t) read the books. When film took Fantasy mainstream, Fantasy became cool (or at least cooler) and the demand for Fantasy stories grew.

Next, we have the Internet, the ubiquitousness of personal computers, and the resulting rises in online communities and self-publishing. With all this technology and the ability to publish stories on FanFiction websites, Amazon, or half a dozen other places, anyone could write any kind of Fantasy about anything from anywhere and share it with anyone. No longer were publishing companies the gatekeepers of literature.

I think the most dramatic change to the Fantasy genre has been the flip from being male dominated to female dominated. According to one research study, the gender demographics for Science Fiction and Fantasy (SFF) readership have been slowly equalizing over the past few decades. The authors report that in 1963, an estimated 92% of SFF readers were male. In 2003, 67% were male. In 2011, 59% were male. And in 2018, 55% were female. I believe that with the juggernaut rise of “Romantasy,” the female readership percentage has grown further since 2018. Currently, Romantasy seems to be the dominant Fantasy sub-genre with its combination of traditional Romance and Fantasy genres. I believe it rose out of the popularity of The Twilight Saga that created a demand for more supernatural romance. As Twilight fans matured, they seem to have been open to more sexually explicit fiction, and authors like Sarah J. Mass and Rebecca Yarros were able to capitalize on this demand with their Romantasy series in the mid-2010s and into the present day.15

I think the message of the Fantasy Diaspora has been that anyone can take part in the Fantasy genre and that there are no rules that can’t be broken. Authors have explored countless new sub-genres (LitRPG maybe being the most “product of its time” one). Twelve-year-olds are writing and publishing Twilight fan fiction on their moms’ iPads. SubStack writers are writing fantasy serial novels. Internet communities are creating new urban legends. The Alt Rock band Twenty One Pilots created the first ever Fantasy album trilogy (2018-2024). YouTube creators write and animate original Fantasy stories (like this cool one about dinosaur people). Fantasy video game franchises abound (Elden Ring, Skyrim, Baldur’s Gate, etc.). Plus, we have many new authors like Jasper Fforde, Rick Riordan, Joe Abercrombie, Susanna Clarke, N. K. Jemisin, Patrick Rothfuss, Brandon Sanderson, Scott Lynch, Cassandra Clare, Jim Butcher and too many more to do the era justice.

Perhaps the sum of all of this is that the question “Who can be a hero?” has been answered.

It seems to be “anyone.”

Future Predictions

And now for a final bit of fun.

Since the Gothic novel and until just before the Fantasy Diaspora when Fantasy went mainstream, the Fantasy genre usually invokes the opposite of prevailing literary trends especially if those trends are naturally mimetic (e. g. There was no strong Fantasy countermovement to Romanticism because that literature was already so unreal, but as soon as Realism reared its head, Fantasy was reinvigorated.)

Now that Fantasy is very much mainstream and often seems to align with the values of our time, a subversive predictive model of Fantasy trends may be obsolete. We are treading new ground.

We may have to wait for the end of Postmodernity (and perhaps a more Realist reaction to it?) to see what Fantasy will do next. But I still believe that Fantasy is a rebellious genre.

So here are my three predictions:

First, as Romantasy and Young Adult Fantasy solidify their tropes and metanarratives, I think they will present ripe targets for satire. We have so many sub-genres being explored now that satire could strike from any angle, but I think these two monoliths (each with some pretty ridiculous tendencies) are begging for a Terry Pratchett-like someone to come along and tear them to pieces. Fantasy as a whole right now is just so sincere and earnest and focused on creating a believable world that I think readers will respond well to a little buffoonery and humor that doesn’t take itself (or anything else) too seriously. We need an author to make fun of the “spiciness” and “chosen ones” of these genres.

Second, contemporary Fantasy features so many hard magic systems that it often reads more like Science Fantasy (a genre where all magic must be explainable). Brandon Sanderson is maybe the best example. But hard magic trades a sense of mystery for clarity, and I’m expecting a resurgence in soft magic systems. This may look like more Magical Realism and stories with just the tiniest bit of magic intruding into everyday lives (maybe we already see this in the work of Neil Gaiman?). Or it may be as extreme as reverie-filled, atmospheric Fantasy like that of George MacDonald. I think if this trend does take off, Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (very atmospheric and thoughtful) will come to be known as the progenitor.

Third, I think we’ll see a reaction against heavy plotting. Plot-focused novels can feel a little generic and often trade depth for novelty and twists. The literary industry already has a (maybe false) binary between genre and literary fiction, and think we’re going to see the rise of Literary Fantasy—books focused on character and tone told in magical settings. These books may return to some of the earlier, atmospheric stories (again, like MacDonald) and provide more thoughtful and contemplative approaches to Fantasy.

Those are my guesses, but who knows what will happen? As it has been since 2,100 B. C. and down through many eras and trends and themes, what Fantasy will be is up to us.

Thank you for reading past the dragon.

And thank you again to Farah Mendlesohn and Edward James for their wonderful book A Short History of Fantasy (2009). This would have been near impossible without their help.

Also, thank you to my wife for allowing the 50+ hours I’ve put into writing this over the last couple of weeks.

My goal in this essay was to delineate and create names for the different eras of Fantasy literature. I’ve done that (mostly) to my own satisfaction, but I know others will have varying and helpful viewpoints. So massive an undertaking cannot be fully accomplished in under 10,000 words.

So my question for you is this: Is there a book or author that (A) you would include in a top 100 list of most important Fantasy stories of all time and that (B) you think I should have mentioned in this essay? (I may add it to my every growing ThriftBooks wishlist.)

Yes, I’m ending a sentence with a preposition. Don’t “at” me, bro.

When I discovered

and devoured his cutthroat, satirical short story collections, I spent a lot of time wondering what school to categorize him in. I never quite figured it out—perhaps he’d like to comment on this for himself and make my whole year? I’ve more enjoyed his work than studied them, but I’m still confident he will have his own subheading in literary history.I’m a little ashamed to say that I’m less of an empathic reader and more of an anthropological reader. Whether I like it or not, it’s hard for me to get as excited about a character’s personal struggle as about how that character’s struggle characterizes the “spirit of the age” or something. Based on An Experiment in Criticism and this other essay I wrote, I’m not sure C. S. Lewis would call me a “true reader,” but if anything redeems my approach to reading, it’s that I’m still reading a story happily without escapist goals. The story I’m enjoying is just more metatextual.

If you think these are too exhaustive, you should quit now. I go into waaaaay more detail on the Fantasy eras. This essay is not for the faint of heart. Sorry, cardiomyopaths.

American Industrialists and inventors remind me of the Tech Bros of our era. So much optimism and forward progress, but so little moral responsibility.

Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. NorrellI (2004) is significant for harkening back directly to the Celtic tradition of Faerie.

Note that Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote (1605) is itself a satire of this genre established by these texts. As a Realist reaction against romanticized Medieval chivalry, it follows the pendulum trend established in the general literary trends.

Jane Austen satirized the Gothic novel in her Northanger Abby (1818) in which the greatest Gothic danger is in believing in Gothic danger.

I didn’t know what “mimesis” meant before I started my research, so I’m not going to let you keep wondering either. It’s basically the copying of something real and trying to stay true to it. Realist literature is Mimetic. So Fantasy literature (the creation of something new) will always be antithetical to mimetic literature.

Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) is a very American response to the Pre-Raphaelites. In it, a single factory worker from late 1800s Connecticut is transported back to King Arthur’s court where he makes a fool of everyone and takes over.

Interesting how many Tolkien acolytes seem to miss this message. Many later Fantasy stories focus on questing for the powerful magical item so as to use it instead of to remove the temptation. Rowling gets it right when Harry turns down the Elder Wand.

As a fun bit of trivia, M & J’s chronological list of significant Fantasy stories is about 1.2 pages long for the 60s and 3 pages long for the 70s.

I could have sworn I saw a quote that said of the Shannara series, “Never has one series owed so much to another as Shannara to The Lord of the Rings.” But I can’t find it anywhere. Anyway, it seems to be the general attitude of critics.

Okay, actually the number of Wiccans in America went from 8,000 in 1990 to 340,000 in 2008. So maybe?

I think Romantasy gets a lot of flak for verging on pornographic (which doesn’t suit my taste in literature and is almost always escapist), but men have been sexualizing women and verging on the pornographic in Fantasy for a long time, so let’s all just take a deep breath and . . . condemn everyone for cheap, titillating tactics.

![A Short History of Fantasy [Book] A Short History of Fantasy [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F51288f40-6313-419b-9440-ed18c6492e59_219x350.jpeg)

Loved this! Do you think that fantasy is inherently tied to mythology? Are there big works of fantasy that aren't tied to a mythologic/religious tradition?

Great job, Clifford! It was a great education. Personally, I think your "Where Next?" predictions are spot on. My writing falls in the second one--mostly "realistic" adventure stories with a touch of "magic." Thanks for the time and effort!