The Actual Point of Literature Most Readers Forget

And how C. S. Lewis's Uncle Andrew is the focus of Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

**This essay contains significant spoilers of the books Piranesi by Susanna Clarke and The Magician’s Nephew by C. S. Lewis.**

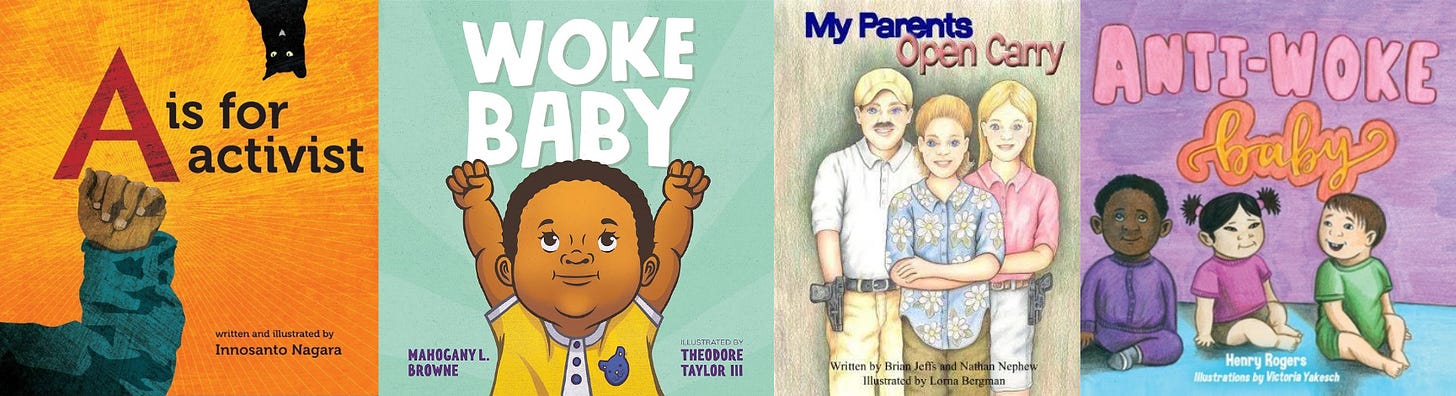

The greatest threat to literature in 2024 is the pragmatist—the person who reads a book and asks, “But what use is it?” Pragmatists rarely read fiction (and definitely not fantasy). If they do read fiction, they scour the book for a moral or a lesson—anything to make the reading experience “worthwhile.” They use books as pawns in censorship-themed culture wars.

And they are responsible for some truly terrifying children’s books covers…

The one thing pragmatists never seem to do is enjoy a story. And this can have a devastating effect on the pragmatist, their children or students, and on the culture at large.

In “Escapists and Intellectualists Can't Experience True Literary Joy,” I discussed two unhealthy, pragmatic approaches to art and stories. Now let’s discuss the progenitor of escapism and intellectualism: pragmatism. And to do it, we’re going to study the interconnected themes of Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi and C. S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew.

Piranesi’s Premise

In Piranesi by Susanna Clarke, a man nicknamed Piranesi (after an Italian painter known for dark and vast etchings of prisons) lives in an endless world of statue-filled halls known as the House. Each hall has three levels. The top floors are full of rain and clouds. The middle floors contain an unending variety of mythical, human, and natural statues. The bottom floors are flooded by oceans and tides and are where Piranesi finds food.

If the House sounds trippy and Borgean, that’s because it is.

Piranesi only remembers the last few years of his life and spends his days cataloging statues in a peaceful awe of the beauty of the House. He calls himself a “Beloved Child” of the House. His friend, the Other, is the only human he has ever met. The Other has a short temper and is condescending to Piranesi. The Other believes magical powers reside in the House.

In fact, the Other (whose real name is Dr. Valentine Andrew Ketterley) kidnapped Piranesi (formerly Matthew Rose Sorenson) out of our world and into the world of the House. Ketterley put him there like a rat in a maze to explore the house to find the magical powers for him. But the magical properties of the House caused Matthew to lose his memories of his former life, so he knows none of this.

The Ketterley Connection

When I read the name “Ketterley,” I remembered the first epigraph of Piranesi:

“I am the great scholar, the magician, the adept, who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on.”

This quote is from C. S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, the prologue piece of The Chronicles of Narnia. And there are many, many similarities between Piranesi and The Magician’s Nephew. Both have . . .

A magic that allows visiting other worlds.

A liminal place between worlds.

A cruel, haughty magician named Andrew Ketterley.

Kidnappings of unsuspecting people to another world by the magician.

There are more, but the most important is that Clarke’s Valentine (Val) Ketterley is clearly based on Lewis’s Uncle Andrew. They are both magicians borrowing someone else’s magic to visit other worlds and who force other people—other “subjects”—to take the risks for them.

Clarke even suggests that the two are actually related, tying her story world into Lewis’s (which I think is a delightfully bold move). She writes that Dr. Val Andrew Ketterley was born in 1955 and was the “[s]on of Colonel Ranulph Andrew Ketterley, soldier and occultist.”

The clues (or more like billboards of evidence) are all there. Apparently Andrew is a family name, and the men of the family tend to be interested in the occult and magic. Clarke goes so far as to paraphrase a line directly from The Magician’s Nephew when she writes, “The Ketterleys are an old Dorsetshire family,” which references Lewis’s line “The Ketterleys are, however, a very old family. An old Dorsetshire family, Ma'am.”

Lewis’s influence is clear on Clarke in an interview with The Guardian: “I found Lewis at a very impressionable age and then he sort of organised the inside of my head.” Not only is Clarke having fun connecting her story to that of her hero, but she’s drawing a thematic connection between the two Ketterley characters.

Uncle Andrew’s Unkind Attitude

Lewis’s Uncle Andrew is a conniving, cowardly, “little, peddling Magician who works by rules and books” without any real talent for magic (as described by the evil queen Jadis). He finds magic dust that he turns into rings that take the user to other worlds. First he sends guinea pigs to the other world with the rings. And when his nephew Digory and Digory’s friend Polly chance into his study, he tricks Polly into touching a ring, flinging her into another world; he then blackmails Digory to go after her.

He does all of this for the sake of his “experiment” as he views himself as a magician/scientist above “ordinary, ignorant people” and common morality. In the most hilarious and self-damning character development I’ve ever read, when Digory confronts him on kidnapping Polly, Uncle Andrew responds:

Oh, I see. You mean that little boys ought to keep their promises. Very true: most right and proper, I'm sure, and I'm very glad you have been taught to do it. But of course you must understand that rules of that sort, however excellent they may be for little boys—and servants—and women—and even people in general, can't possibly be expected to apply to profound students and great thinkers and sages. No, Digory. Men like me who possess hidden wisdom, are freed from common rules just as we are cut off from common pleasures. Ours, my boy, is a high and lonely destiny.1

But Uncle Andrew’s pride continues. When Digory questions Uncle Andrew’s motives for wanting to send other people out of the world, Uncle Andrew defends it as a scientific investigation. But he would never go himself:

“Me? Me?" he exclaimed. "The boy must be mad! A man at my time of life, and in my state of health, to risk the shock and the dangers of being flung suddenly into a different universe? I never heard anything so preposterous in my life! Do you realise what you're saying? Think what Another World means—you might meet anything—anything.

This brings us to where Clarke sourced her epigraph:

You don't understand. I am the great scholar, the magician, the adept, who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on. . . . the idea of my going myself is ridiculous. It's like asking a general to fight as a common soldier. Supposing I got killed, what would become of my life's work?

Uncle Andrew’s greater “destiny” means he sees himself as greater than others and above common moral laws. He must continue his experiment but only if he can send others to do the dirty work just as Clarke’s Val Ketterley uses Piranesi to explore the House for him.

Piranesi’s Pragmatic Pal

One can see how in Piranesi Clarke isolates Uncle Andrew’s character from The Magician’s Nephew and builds a new story around him. She gives him Piranesi as a foil and makes that abrasive relationship the point of her entire book.

And their greatest difference is in how they relate to the house.

Val Ketterley fails to see the beauty in the House. He says to Piranesi, “But there isn’t anything powerful. There isn’t even anything alive. Just endless dreary rooms all the same, full of decaying figures covered with bird shit.” Instead, all he cares about is finding and taking “a Great and Secret Knowledge hidden somewhere in the World that will grant us enormous powers once we have discovered it.”

Piranesi is the opposite. He marvels at the House. He ponders the statues. He appreciates the beauty of this endless, magical world: “I have known for many years that the Other does not revere the House in the same way I do, but it still shocks me when he talks like this. How can a man as intelligent as him say there is nothing alive in the House?” He goes on to list the animals and plants in the seas of the lower floor, the birds (and the two of them) in the middle halls. And he takes offense at the Other calling them all the same. No two statues are the same. The architecture varies hall to hall. The tides come and go.

He even decides to broach the subject with the Other when he realizes that

[T]he Search for the Knowledge has encouraged us to think of the House as if it were a sort of riddle to be unravelled, a text to be interpreted, and that if ever we discover the Knowledge, then it will be as if the Value has been wrested from the House and all that remains will be mere scenery.

Citing Owen Barfield (a friend of Lewis’s) in an interview with Church Times, Clarke says, “Modern man looks out at the world, but there’s this gap between us and the world . . .” But she wanted that “Piranesi should feel like he perfectly belonged in the world in which he found himself, and that the world was benevolent, and that it really cared for him, and he for it.”

But the Other cannot appreciate all of this because he only cares about finding the useful “Great and Secret Knowledge” that will help him dominate other humans in our world.

If you’re not familiar with historical modernism, one of its foremost qualities was the belief that man could overcome nature to progressively make the world a better place. Byproducts of this attempt include the atom bomb, eugenics, pollution, and man’s increased separation from nature.

To understand what this separation from nature looks like, consider that if I find a spider in my house, rather than let it eat other more annoying bugs, I kill it and then pay an exterminator to kill the other bugs for me.

Modern man is in a war against nature, and Val Ketterley is the quintessential modernist. While Piranesi enjoys the house, Ketterley only wants to use it. Another character describes him this way: “But Ketterley is an egotist. he always thinks in terms of utility. He cannot imagine why anything should exist if he cannot make use of it.”

Matching Magicians

Thus, thematically, Uncle Andrew Ketterley and Val Andrew Ketterley become one.

When Uncle Andrew finds himself watching the lion Aslan sing Narnia into existence, he looks at the magnificent spectacle entirely pragmatically:

If I were a younger man, now—perhaps I could get some lively young fellow to come here first. One of those big-game hunters [to kill Aslan]. Something might be made of this country.2

Uncle Andrew becomes elated when he sees a crossbar fall onto the Narnian ground and immediately grow into a full lamppost:

I have discovered a world where everything is bursting with life and growth. Columbus, now, they talk about Columbus. But what was America to this? The commercial possibilities of this country are unbounded. Bring a few old bits of scrap iron here, bury 'em, and up they come as brand new railway engines, battleships, anything you please. They'll cost nothing, and I can sell 'em at full prices in England. I shall be a millionaire.3

Faced with beauty and art (in Aslan’s song and creation of the world), Uncle Andrew wants to grow an industrial business. In Piranesi, when faced with beauty and art (statues and architecture), Val Ketterley only cares for magical powers.

Neither gets what they want, and they fail to appreciate the fantastic environment for what it is. Instead they want to use it for something else.

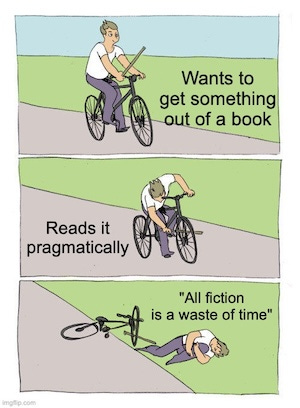

Forcing It vs. Feeling It

Lewis discusses this concept in his short book An Experiment in Criticism: “The distinction can hardly be better expressed than by saying that the many use art and the few receive it.”

According to Lewis, some readers of literature are unable to fully appreciate a story because they always have an ulterior motive for reading it. They believe there has to be a moral or a way for them to show off how well read they are. Or they have to be able to escape into it and to forget their present woes. Whatever the use, there has to be some use. Otherwise, why read it?

They see the story as a means to an end. And because of this, the story can never work on them. They never feel anything they haven’t felt before. They never grow in a way they didn’t expect. Even those readers looking for morals only find morals they already know. Pragmatic readers are too pragmatic to be surprised.

Lewis’s healthy group of readers simply read the story. They experience it. They appreciate it. They think about it. They live in it. And because they are not trying to imprint themselves and their values and their goals onto it—to use it—they can receive what the story has to share.

Lewis would agree, I think, that pragmatism when taking in art “[fixes] the ultimate intention on oneself. [It treats] as a means something which must, while you play or read it, be accepted for its own sake.”

Endings and Exhortations

And how do the two Andrew-named pragmatists fare in the books in question?

Val Ketterley drowns in a House he never bothered to understand or respect. Uncle Andrew spends the entire adventure to Narnia muddy, miserable, and unintelligible to the talking beasts of Narnia who think he might be a plant.

I think it’s a little drastic to suggest these as metaphorical fates for all pragmatists who try to use art.

It’s easier to imagine most pragmatists never realizing the consequences they suffer. They just go on thinking how clever they are as they live self-contained lives with few existential challenges. They die smug and self-satisfied that they never wasted their time.

But the loss is theirs. They never lived life through the eyes of someone else or encountered an idea they weren’t expecting. They never let a story fill them with a sense of wonder or pathos. They never received what a book—what another author (maybe anyone?)—had to share.

And I think that’s very sad.4

Don’t settle for literary pragmatism. Let stories and art be what they are. Be humble. Be open. Experience books. Like Piranesi, receive what the House—what stories—have to give.

Thanks for reading past the dragon!

I couldn’t find a good place to put it in the essay, but this whole topic reminds me of another favorite quote from Narnia:

"Use?" replied Reepicheep. "Use, Captain? If by use you mean filling our bellies or our purses, I confess it will be no use at all. So far as I know we did not set sail to look for things useful but to seek honour and adventures.

Lewis released The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in 1952, and if I replace “seek honour and adventures” with “receive stories,” you have the entire thesis of his 1961 book An Experiment Criticism.

But also, can I say how much I loved Piranesi? It’s a fantastic book. So well written. So compelling. So powerful. Mark my words: this is one of those books that will still be being read 100 years from now.

Thank you for reading! Do you have book you felt you were able to receive without being pragmatic about it? Let me know the name and author, and I’ll add it to my ThriftBooks wishlist.

Uncle Andrew’s statement is obviously an awful thing to say, but I can’t help laughing. I think Lewis’s ability to show the ridiculousness of vanity and sin is a great strength.

Incidentally, when Val Ketterley kidnaps Matthew Rose Sorenson, he says, “Forgive me for not saying anything before now . . . but I really am delighted to see you. A young, healthy man is just what I wanted.” Uncle Andrew got his wish! Though Val has to bring the gun himself in the third act of the book.

I can’t help but laugh every time I read one of Uncle Andrew’s tirades about his own moral superiority or the “commercial possibilities” of Narnia. Lewis does such a good of lampooning utilitarianism and modernistic tendencies with him. And in a children’s book too! And without being preachy or overbearing. And it’s because we really believe in the character of Uncle Andrew and (I think) like him in spite of himself. Even Lewis lets him down gently in the end: “in his old age he became a nicer and less selfish old man than he had ever been before.”

I worry too that most of our politicians and educators are pragmatists as well who go on infecting young, impressionable readers with this stunted approach to literature. American politicians posture over censorship and “politically charged” books. American educators cut out bits of literary texts to use as exercises to prepare students for achievement tests. No wonder American literacy is below the world average. Why bother reading if that’s all there is to it?

Zombies. Pragmatists mistake the social experience of coffee for a caffeine delivery exercise tantamount to swallowing no-doze. And it's even worse with literature.

I'm currently reading "Lilith" by George MacDonald. If ever there was a potent and fulfilling story that had precisely zero actionable takeaways, "Lilith" would make the short list.

I had to stop early, as I’ve not partaken Piranesi. However, I wanted to concur that Lewis produced such rich character moments in Nephew. His reach back explanation of Andrew’s strange (to the reader) point of view in Chapter 10 is among my favorite: “Now the trouble about trying to make yourself stupider than you really are is that you very often succeed.” I have to ask myself if I’m doing that from time to time.