Tolkien Gives George R. R. Martin the Smack Down or Why Happy Endings in Fantasy Are a Requirement

Pt. 4 on Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories" with Eric Falden: Consolation

Welcome to Week Four of and I dissecting J. R. R. Tolkien’s 1947 essay “On Fairy Stories.” So far, Eric has written about Tolkien’s definitions of good Fantasy storytelling and world building, I’ve written about how Fantasy helps us recover our sense of wonder, and last week Eric discussed how true Escape (not cheap Escapism) plays an important role in quality Fantasy. I’d recommend reading these before proceeding.

Shouldn’t Fantasy Be Realistic and Thus a Total Bummer?

Let’s talk about something that’ll really trigger George R. R. Martin and the rest of the Grimdark/Gothic/Horror Fantasy contingent of our genre family:

According to J. R. R. Tolkien, happy endings are the most important part of good Fantasy.

Tolkien even writes in “On Fairy Stories,” “Almost I would venture to assert that all complete fairy-stories must have it.”

😱

The masses will disagree, right? Aren’t happy endings naive? Gauche? Trite? Out of touch? Simplistic? Dated?

Considering the state of our gritty, chaotic world, I’m not surprised some readers think so. If the world is so full of war and suffering and conflict and Katy Perry albums, how can we accept stories that end happily?

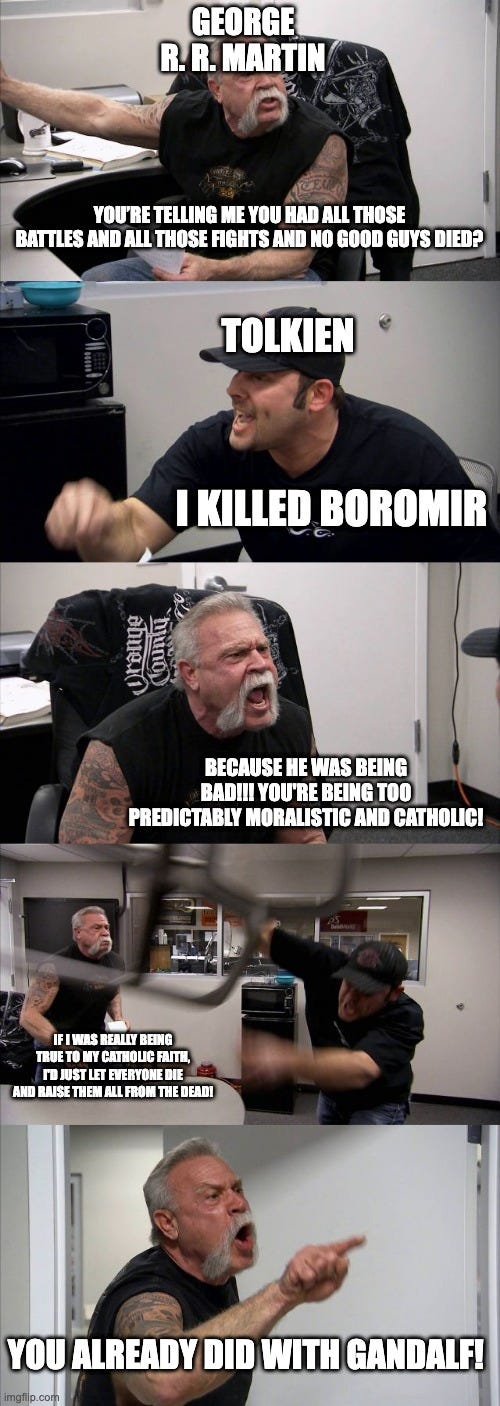

After Tolkien released The Lord of the Rings in the 50’s, authors immediately began reacting against his seemingly idealized stories,1 and we saw the slow rise of Dark Fantasy—Fantasy set in amoral worlds that ended tragically and contained frightening or disturbing images. Then along came George R. R. Martin with his A Song of Ice and Fire who popularized Grimdark Fantasy—even more tragic Fantasy set in an even more amoral, even more disturbing, and even more chaotic world.

Both Dark and Grimdark Fantasy are anti-Tolkien in construction AND intention. Martin has spoken about the unrealistic assumptions that lead to happy endings in The Lord of the Rings, and the biggest fans of Grimdark are those who find Middle-Earth unbelievable.

And I get it. When was the last time Western society saw a happy ending? Is the War on Terror over? Aren’t people still getting COVID? Was the War on Drugs won? Russia’s still a pain in the ass. Katy Perry is still making music. Nothing gets better. We just move from unsolvable crisis to unsolvable crisis.

And for a Secularist/Naturalist/Atheist Fantasy author2—someone who does not believe in the supernatural—all these terrible things in our world are the realest reality, as real as real gets. Life begins and ends in a world of pain and failure with only brief reposes of temporary happiness, and that’s it3. And that seems to be the underlying, informing belief of Grimdark Fantasy: the world sucks, so let’s fight it out. Might makes right.4

But what are these pessimistic authors reacting against? What is it about Tolkien that inspires anti-genres? How different can Tolkien be from these guys? I mean, they’re all writing about swords and dragons and quests, right?

You have no idea.

Reality vs. Really Real Reality

Check out the first Tolkien verse from the Epic Rap Battle of History between Martin and Tolkien:

In it, Tolkien raps about happy endings and realism in Fantasy, but the writers, EpicLLOYD and Nice Peter, don’t get Tolkien quite right . . . at all . . . like . . . it’s really bad:

We all know the world is full of chance and anarchy,

So, yes, it’s true to life for characters to die randomly,

But newsflash: The genre’s called fantasy.

It’s meant to be unrealistic, you myopic manatee.

If you’ve read “On Fairy Stories” or much by Tolkien, you probably felt your stomach drop when he rapped that Fantasy is “meant to be unrealistic.”

What?

You think the guy who created a whole language, history, mythology, and geography for his secondary world was trying to be unrealistic?

Good golly, guys. In “On Fairy Stories,” Tolkien hallows achieving “the inner consistency of reality” and explicitly writes about “every writer making a secondary world . . . hopes that he is drawing on reality.”

The surprising truth here is that Tolkien wasn’t anti-reality. He was pro-realer-reality.

Tolkien’s Christian Faith

To understand this, we need to understand the thing most important to him: his Catholic Christian faith:

Tolkien was a staunch Catholic who believed in the Christian Gospel (he calls it the Evangelium in “On Fairy Stories”) in which God created mankind and gave it a paradise to live in. But men sundered their relationship with God by deciding to follow their own hearts, leading to the advent of every sin from white lies to genocide and sealing their fate of death and eternal suffering separate from God. But God had grace on us and came to Earth in human form as Jesus Christ and took the consequences on Himself by dying and internalizing that separation. Thankfully, the punishment of all mankind is nothing compared to God’s goodness and power, and once the price of death was paid, God resurrected Jesus. Their sin forgiven, mankind has a chance to reunite with God, to be on his side when He returns to Earth to rule, and to spend eternity with Him in a new paradise.

The big takeaway here: Christians believe in happy endings. The blueprint of the Christian faith and narrative is that things are meant to be good and will be good again; there’s no such thing as a permanent sad ending. In the real world, Good always wins even if Evil prevails for a moment, and endings are always happy because God has made happy endings the default of reality. Even death has no power over God’s followers because death is just a doorway to something better.

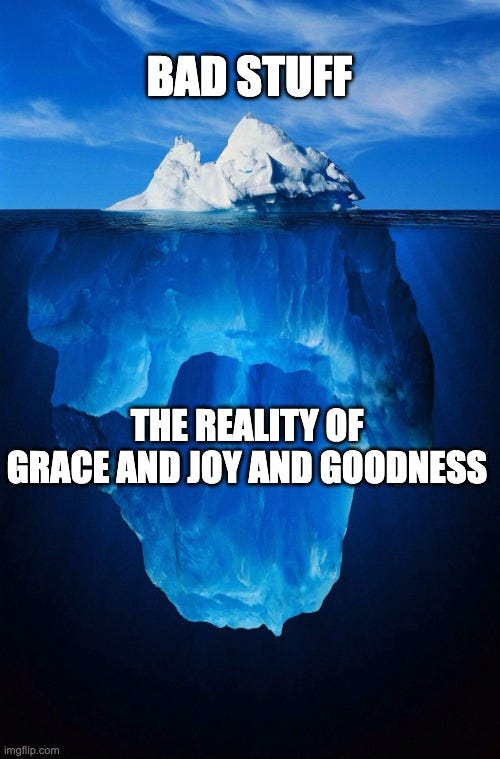

However, for a Naturalist, there is no overarching moral power, there is no eternal significance to our actions, and death ends everything. So it shouldn’t surprise us that Fantasy honestly written by Naturalists would be tragic and dark.5 Or that they’d take umbrage with Tolkien’s happy endings. But Tolkien might say that these authors are only seeing “through a glass, darkly” because they aren’t seeing the bigger picture of reality; they’re focusing on the surface level.

Narrative Consolation in Fantasy

But Tolkien’s happy endings don’t just happen, and they are not achieved easily. Tolkien acknowledges the existence of “dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure.” That’s Gandalf dying, the Shire being industrialized, Frodo refusing to throw the Ring in the fire, Boromir trying to take the ring, Theoden dying, the Hobbits going without second breakfast, and many other equally terrible moments in The Lord of the Rings. Plus, if you’re tempted to think Tolkien was a blind optimist living a charmed life, I’ll hazard a guess that his life was harder than yours. Remember that he was an orphan by age twelve, fought in the trenches in World War I, and lived through World War II.

But Tolkien still believed in the goodness of ultimate reality. And this appears in his writing with his third and most important value of Fairy Stories and Fantasy: the “Consolation of the Happy Ending,” which he says is achieved through “Eucatastrophe”— “the good catastrophe” or a “sudden joyous ‘turn’” in the narrative.

Tolkien describe Consolation and Eucatastrophe this way:

In its fairy-tale—or otherworld—setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief. It is the mark of a good fairy-story, of the higher or more complete kind, that however wild its events, however fantastic or terrible the adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the “turn” comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears, as keen as that given by any form of literary art, and having a peculiar quality.

I encourage you to read that quote again, but the gist is this: Fantasy has a unique ability to take readers through awful sorrow, pain, and tragedy and then to surprise us with the overwhelming power of good to defeat evil, and this is a reflection of the Gospel, of God coming out of nowhere as Jesus Christ to save mankind—the Evangelium. This is Tolkien replicating the real world. This is him writing realistic fiction.

And a great example is Gandalf and Eomer in the films (only Gandalf in the books) bringing a contingent of Rohirrim down the hill to save Helm’s Deep just when all seems lost.

Tolkien believed the proper form of a Fantasy story is not to deny evil or to relish in evil but to persevere through that evil to build up to the turning point when good comes marching in and obliterates evil—the eucatastrophe that is so beautiful and so good and so powerful that it makes us cry for the joy it makes us feel.

And this joy we see is not simple happiness. It is “Joy beyond the walls of the world”—our world, the supposedly “real” world. It’s reflecting the joy of the underlying truth of the Evangelium, the Gospel of God who stepped down from Heaven to save mankind from itself.

And The Lord of the Rings is replete with moments in which Tolkien captures the Consolation of the happy ending and the “sudden joyous ‘turn’” of Eucatastrophe. Among the many, there’s Tom Bombadil saving the hobbits from Old Man Willow, Gandalf returning to Helm’s Deep, the Rohirrim and the Army of the Dead showing up at Minas Tirith, and (most heart-thrillingly to me) the returning Hobbit warriors freeing the Shire,

What do these all have in common? If you look at them from the perspectives of the people in the trenches—the soldiers without hope, staring down their own deaths—it is “a sudden and miraculous grace” as Tolkien puts it. They are pulled back from the brink of death and dyscatastrophe to be given hope by a rescue from a powerful force of goodness.6

Is that not Tolkien playing out the Gospel—the Evangelium? And is that not him being as true to reality—as realistic—as he possibly can?

For Tolkien, Consolation, Happy Endings, and Eucatastrophe are as real as reality gets because God made the world to end happily.

Tolkien’s philosophy of happy endings also reminds me of a great moment from The Avengers in which Hulk beats up Loki and tosses him aside muttering “puny god.” The Avengers had been fearing Loki and his power the whole film, and now some green guy comes along and beats him up without a second thought. It’s that kind of moment when all the nightmares, all the fear, and all the anxiety are destroyed and what we feared to be real—the death and destruction—turn out to be nothing but a “puny god.”

This also reminds me of George MacDonald’s line in C. S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce:

Yes. All Hell is smaller than one pebble of your earthly world: but it is smaller than one atom of this world, the Real World. Look at yon butterfly. If it swallowed all Hell, Hell would not be big enough to do it any harm or to have any taste.

That’s what Tolkien is talking about too—the unforgettable awesomeness and inevitability and hugeness and realism of Good. As Frodo says in The Two Towers, “The Shadow that bred [the orcs] can only mock, it cannot make: not real things of its own. I don't think it gave life to the orcs, it only ruined them and twisted them.” Evil exists, but it is pathetic compared to Good, and Tolkien believed Fantasy stories with their unique settings and customizable parameters are particularly suited—even have a responsibility—to showcase this.7

Remaking Our World with Fantasy

In the epilogue of “On Fairy Stories,” Tolkien writes that a Fantasy author whose world is consistent within itself and with Reality will contain some measure of Joy/Consolation of Happy Ending and that the resulting eucatastrophe “may be a faroff gleam or echo of evangelium in the real world.”

Translation?

Good Fantasy will echo the same joy found within the Gospels.

But it’s not just Fantasy that reflects the Gospels. Tolkien also claims that God used the features of a Fantasy story in his plan to save mankind:

The Gospels contain a fairy story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. . . . [A]mong the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy.

So, if a good Fairy Story echoes the joy of the Gospels and the Gospels echo Fairy Stories . . . What is the result?

But [the Christian story] is supreme; and it is true. Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused.

That last part—“Legend and History have met and fused”—is the key conclusion. Fantasy can be true to the deeper reality of the world because the deeper reality of the world is a true fairy story!

The result?

God Himself, according to Tolkien, has hallowed Fairy Stories and allowed the Fantasy author a special role: “[H]e may now, perhaps, fairly dare to guess that in Fantasy he may actually assist in the effoliation and multiple enrichment of creation.” By Recovering a view of the real world, providing Escape to realer reality, and showcasing joy through Consolation, the Fantasy author (sub-creator) can assist God in making the world a better place.

Thank you for reading past the dragon.

Be sure to check out Eric Falden’s Falden’s Forge to get the final installment of this discussion of “On Fairy Stories” by Tolkien. We’ll be highlighting comments and insights from the Substack writer’s community.

Reading this section of “On Fairy Stories” did make me a little weepy. It’s so overwhelming and beautiful to understand Tolkien’s vision for sub-creating, and it’s amazing to me as a Christian to see how writing a Fantasy story can be an act of worship and reformation. I can see why Tolkien obsessed over every detail of Middle-Earth; there was a lot at stake. As I work on my own Fantasy story, I hope I can hold to the same values.

My question for you is this: what scene (book or movie) gives you that pang of joy and relief? My favorites—hands down—are the Scouring of the Shire in The Lord of the Rings books and Eomer coming over the hill to Helms Deep in the movies. I’d love to hear what gets you in the feels.

There might be some Dark Fantasy-esque stories before 1954 when The Fellowship of the Ring came out, but Dark Fantasy didn’t solidify as a genre until decades later. Dark Fantasy authors, however, did start contesting the happy endings of The Lord of the Rings almost immediately, laying the foundation for the genre. I’d count Michael Moorcock as one of the earliest anti-Tolkien Dark Fantasy authors.

I think Martin is an Agnostic, but he writes like a Naturalist. Plus, my understanding is that most Agnostics are just Naturalists wanting to leave their options open. But if Martin’s worldview is anything like the underlying, core principles of his novels, he’s a Naturalist and practically Nietzschean.

If anyone wants to argue this point, “check your privilege” first. Most people who want to claim earthly life is overall good are in the top 5% of earners worldwide and were born into a rich country that thrives on cheap labor markets in the third world.

Curiously, this statement is the antithesis of T. H. White’s 1958 book The Once and Future King, a book about solving the problem of people thinking that might makes right. Funny how we can go so far but come right back to where we started.

I suppose a Naturalist could go full-Nietzschean and find philosophical significance in telling the universe, “Screw you. I’m here. Deal with it.” But the Ubermensch dies too . . . Or Naturalists will sometimes zoom in on some smaller, happier aspect of the world and crop out the sorrow and tragedy.

Don’t even think about calling this Deus Ex Machina. I wrote about 1,000 words on why Tolkien actually rarely indulges in ol’ DEM, but it just didn’t fit in the essay, so I had to delete it. I’m no mood to put some upstart Tolkien-hater in their place over this.

While Tolkien has convinced me of this, I recognize not everyone will agree with Tolkien. I’d be fascinated to hear what those who disagree belief the philosophical good of Fantasy is.

Comparing the work of a living author to a dead one is unfair to them both.

That being said: I am extremely sick of the amount of nihilism in contemporary film and television and have replaced it in my own writing with optimism, though tempered by reality. There is still a place for this philosophy in the media, but it is ignored and undervalued by being compared too much to reality, which is not a fair assessment.

I think we have to remind ourselves from time to time that On Fairy Stories was published long before Lord of the Rings and so should not be read as a defense of it. And I think that by the time Tolkien got to the end of LOTR he had learned something that he didn't know when he wrote On Fairy Stories.

Let me step back and suggests that there are four kinds of endings, not two. There are the two that recognize the moral order of the universe, the comic and the tragic, and the two that deny it, which are the erotic (life is meaningless but ends in pleasure) and the chaotic (life is meaningless and ends in pain).

But, of course, if you don't acknowledge the moral order of the universe and look only at the physical aspect of life, you recognize that there are no final erotic endings. You may transit through the erotic, but real endings are chaotic.

Comedy is the story that acknowledges the moral order of the universe and ends in joy. Tragedy is the story that acknowledges the moral order of the universe but ends in sorrow, as least in the present world. But as far as this life is concerned, the comic ending is as transitory as the erotic. It all ends in tragedy, and our hope is in the next life. And this leads us to what is in many ways the noblest of endings, the redemptive tragedy.

And I think that by the time Tolkien was wrapping up the end of The Return of the King, much of which is comic in tone (and the slightest and most eccentric part of the work) that he must have realized that there could be no comic ending for Frodo. His redemptive sacrifice has come at the expense of a wound that will not heal (a not uncommon fairytale motif) and he cannot return to the life he set out to preserve in his beloved shire. He must go to the Gray Havens and pass over the sea. To have healed Frodo, body and mind, would have been to cheapen all that had gone before. The dignity of tragedy can and sometimes must prevail in fairytales.