The Most Disappointing Fantasy Novel to Ever Break the Genre

And How It Insults Modern Fantasy Readers

What do readers want from a good Fantasy book?

Based on Goodread’s top 2024 Fantasy Releases list, I’d guess thorough world building, heroic characters, technical magic systems, a couple mythical beasts, and a liberal sprinkling of smut.

But most of all, I think fantasy readers want to get lost in a larger-than-life, other-worldly story. They want escape. And they’re willing to commit. The highly popular House of Flame and Shadow by Sarah J. Maas has 848 pages, Ruthless Vows by Rebecca Ross has 432, and Wind and Truth by Brandon Sanderson has 1,344 (because of course it does).

In contrast, the novel I’m going to convince you to read in this essay is only 183 pages. Its world building is sparse. Its characters are average. There is no magic system. There’s only one mythical beast, but it’s pretty disgusting and hard to describe. And while there is sex, it’s not very sexy.

And all of this from one of the greatest authors to ever write Fantasy.

What was Ursula K. Le Guin thinking?

Ursula K. Le Who?

UKLG was born in 1929 to an anthropologist father and a writer mother. She grew up in the Golden Age of Science Fiction and is best known for taking the genre to new literary heights (The Left Hand of Darkness, The Word for World Is Forest, The Dispossessed, The Lathe of Heaven), but she also wrote fantasy and produced one of the all-time great High Fantasy children’s series: The Earthsea Cycle.

And in 1980 she published another oft-forgotten and little-known fantasy book called The Beginning Place. It’s the story of two troubled young people from an American Midwest town who discover a portal to another world where it’s always evening and where an unknown evil threatens to destroy a mountain village.

Sadly, The Beginning Place only has a 3.53 out of 5 stars from readers on GoodReads. And the number one complaint is that it’s boring. A few examples:1

“Boring” seems to summarize the negative feelings about The Beginning Place because, as Betsy above learned, it takes a modicum of effort to read this book.2

There’s a lot of literary-level description. Le Guin’s fantasy world isn’t exciting. There are no plucky hippogryph friends or sexy elves or magical sword fights. There’s no *ahem* burning of metals inside of one’s stomach to activate very specific, arbitrary magical powers.3 Heck, even the evil beast is ugly. It’s not a cool, fire-breathing, scaled, giant lizard that tells riddles. Just a hard-to-see, pale giant with pointy boobs.4

But you know what there is a lot of?

Well developed characters with relatable, important problems. Thoughtful narrative development. Poetic description. “Moral resonance.” And incisive, powerful themes. And, sure, the plot drags once in a while. Woodland streams aren’t going to describe themselves, people. But you know what Le Guin is doing most of the time when things seem to slow down? She’s paying attention to the actual plot.

You see, this isn’t actually a story about discovering a new world or fighting a devious evil.

It’s about Hugh and Irene—two characters with real problems—who find the fantasy world of Tembreabrezi but who have to learn that Tembreabrezi is not the solution to their problems.

The Main Characters

Hugh Rogers is a fat, 20-year-old man trapped by his mindless job and his controlling mother. He wants to be a librarian, but his mother manipulates him into living with her by accusing him of cruelty and selfishness if he does anything she doesn’t like. One night he has a mild panic attack and starts running until he accidentally discovers “the beginning place”—the portal to another world where he finds a dusky forest, a refreshing stream, and an otherworldly peaceful aura. In this other world, time runs slowly, so he won’t be missed, and the eternal summer evening atmosphere lets him escape from his life.

Irene Pannis is also in a tough situation. Her father died when she was young, and her mother has an abusive husband who tries to flirt with Irene. Her living situation is crumbling as her two best friends/housemates are breaking up. She doesn’t have much money and isn’t sure where she’ll go next. She can’t get her mother to leave her husband, and she feels cut off from everyone. The other world was an escape she discovered years ago—a peaceful place she could rest. But she has also explored further and found the peaceful mountain town of Tembreabrezi where she visits to feel like she belongs somewhere.

The Plot

*HERE BE SPOILERS! BE YE WARNED!*

Hugh and Irene first meet when Irene discovers that Hugh has “trespassed” into her “ain country” and tries to scare him off. Hugh can’t let go of his new respite and keeps coming back.

Their stories converge further when they both end up in Tembreabrezi where they hope for further affirmation and belonging. Irene wants to be loved by the Mayor of Tembreabrezi who is always formal and cold with her. Hugh develops a puppyish crush on the town noble’s daughter. But they both learn more about how the town has been cutoff from “the city” (the capital of their land) by some unspeakable evil and sense of dread and fear. No one can go in or out of the town, and Tembreabrezi is slowly losing everything.

The townspeople (for some reason) think Hugh’s the chosen one who must free them, so they give him a sword and send him off to defeat the unspeakable evil. Hugh is desperate to break out of his grocery checker skin and prove himself a man to the noble’s daughter, so he agrees. Irene is jealous the townspeople never considered her the chosen one and volunteers to lead Hugh up the mountain to the danger.

But there is little heroism in this quest. Le Guin builds tension with dark imagery and short, choppy sentences:

“The hedgerow had given place to forest. Dark branches met overhead. The road was walled and roofed by tree trunks, branches, leaves. A tunnel. Glimpses of sky between the branches. The heavy, ferny odor of the forest. Something huge, pallid loomed by the road ahead. As Irene’s heart lurched, her mind said, it’s the boulder, calm down, it’s only the boulder by the high trail. . . . Only now, speaking, though she spoke barely above a whisper, did she hear the silence. The wind had died. Nothing moved. It was like deafness. There was no sound.”

And as quickly as he got swept up into the adventure, Hugh begins to realize that something is amiss: the heroism is a veneer. He says, “Damned sword keeps tripping me. . . . It’s all fake. . . . Playacting.” When Irene asks him what he means and isn’t he supposed to use it to fight something, he responds, “I don’t know.” And Hugh admits that he doesn’t really know what they’re looking for.

They keep marching up the mountain, and do find an evil creature, but its otherworldly voice and nightmarish aura of fear sends them running for their lives. They realize that they are not in a questing fairytale to kill the beast and free the townspeople. In fact, the town people sent them as bait and sacrifice to appease the beast. Hugh and Irene debate just leaving for their own world but get lost and, as though compelled, end up at the beast’s cave.

Crazed by the aura of fear, angry at being betrayed, and tired of being pushed around their whole lives, they attack the creature. Irene draws it out, and Hugh stabs it but is crushed beneath its weight. He survives but is seriously injured, and the two begin working their way back to the “beginning place.”

Along the way, they fall in love and have sex. When they (barely) make it back to our world, Hugh is taken to the hospital, and Irene goes with him. Hugh’s mother disowns Hugh, Irene finds a new place to live, and the two resolve to build a better life together.

The Vibes

My first love for The Beginning Place comes from the atmosphere. UKLG begins the book with this literary, tour de force description of Hugh’s job:

“‘Checker on Seven!’ and back between the checkstands unloading the wire carts, apples three for eighty-nine, pineapple chunks on special, half gallon of two percent, seventy-five, four, and one is five, thank you, from ten to six six days a week; and he was good at it. The manage, a man made of iron filings and bile, complimented him on his efficiency. The other checkers, older, married, talked baseball, football, mortgages, orthodontists. They called him Rodge, except Donna, who called him Buck. Customers at rush times were hands giving money, taking money. At slow times old men and women liked to talk, it didn’t matter much what you answered, they didn’t listen. Efficiency got him through the job daily but not beyond it. Eight hours a day of chicken noodle two for sixty-nine, dog chow on special, half pint of Derry Wip, ninety-five, one, and five is forty.”

UKLG perfectly encapsulates the experience of an underpaid, rushed, dead-end job. And when Hugh discovers the beginning place, the contrast is strong:

“At the root of the quietness was the music of the water. Under his hand sand slid over rock. As he sat up he felt the air come easily into his lungs, a cool air smelling of earth and rotten leaves and growing leaves, all the different kinds of weeds and grass and bushes and trees, the cold scent of water, the dark scent of dirt, a sweet tang that was familiar though he could not name it, all the odors mixed and yet distinct like the threads in a piece of cloth, proving the olfactory part of the brain to be alive and immense, with room though no name for every scent, aroma, perfume, and stink that made up this vast, dark, profoundly strange and familiar smell of a stream bank in late evening in summer in the country.”

It’s an impressive tone to maintain, and UKLG uses it to give the other world its own personality throughout.

Many Fantasy authors are competent world builders, but I think few are talented as atmosphere creators. In The Beginning Place, UKLG treats her prose and her descriptions like poetry, and it makes for a beautifully worded book, like a cut diamond reflecting all the colors she wants her reader to see.5

But what does she want us to see?

A Context of Escapism

UKLG grew up on the cold, hard streets of the tail end of pulp Sci-fi and Fantasy in the 40’s and 50’s.6 These stories were sensationalist and printed in cheap magazines on cheap paper. Their marketing relied on images of sexy female victims being rescued from otherworldly creatures by grim-faced, muscular space captains or barbarian warriors.

Having quite a bit of self-respect and intelligence, UKLG quickly realized that these stories were predominately wish-fulfillment and escapist. As I point out in my “The 8 Eras of Fantasy Literature: A Short History of Magical Subversion and Rebellious Storytelling,” Le Guin felt “that most pulp authors delivered up imaginative but empty ideas that lacked ‘moral significance.’” And as quoted in my essay “The True Difference between Sci-Fi and Fantasy That No One Talks About,” Le Guin says in “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown” (1975) the “entire object of science fiction” used to be “the invention of miraculous gadgets, the relation of alternate histories, and so on.”

Pulp Sci-fi and Fantasy were about tropes and escapism and novelty and giving the people what they wanted.

In the face of all of this, when UKLG wrote Science-Fiction and Fantasy, she eschewed escapism and barreled into heavy topics. She tackled gender differences in The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) and colonialism in The Word for World Is Forest (1972). And her A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) (a book written for children) explores the main character’s relationship to his own evil nature.

But around her, the Fantasy craze of the 60’s and 70’s brought on by the 1956-158 publication of The Lord of the Rings was burning bright, and readers were demanding more and more Pop Fantasy. And this naturally led to a lot of escapism and pulp-worthy Fantasy novels that went nowhere and provided none of Le Guin’s cherished “moral resonance.”

At this time, too, The Lord of the Rings awoke a desire in audiences for a really deep Fantasy world experience, a desire to dive into lore and to get lost in another world. After all, this was the time of the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Sexual Revolution—it was easy to want an escape from dangers, fears, and complexities that many didn’t want to grapple with or felt they couldn’t resolve. And with this came an early iteration of the rise of fandom. People dressed as their favorite characters. The first Comic Con occurred in 1964. Readers were obsessed with the lore and descriptions of other worlds. The call for expansive world building and mega series was answered by authors like Terry Brooks and Anne McCaffrey and Michael Moorcock and their legions of sequels. Avenues of escape opened all around.

But this desire for escape rankled Ursula K. Le Guin. She was a woman who faced head on every problem she could find. And I believe the state of the Fantasy genre inspired The Beginning Place.

The Ultimate Metafantasy

The Beginning Place is a metafantasy. It’s a Fantasy about the state of Fantasy and about how readers read Fantasy stories. She must have known it wouldn’t be received well because she intentionally wrote the opposite of what everyone wanted.

You want expansive world building? Nope. Just one mountain and a village.

You want heroes who dominate in battle? Nope. Two frightened young people in over their heads.

You want a riveting narrative? Let’s describe the groceries and the stream for a while.

You want magical powers? No, these guys barely know what a sword is.

You want a climactic ending? What about dragging a big dude with broken ribs through the woods?

I believe UKLG intentionally wrote a Fantasy novel that subverted the popular expectations of the genre and forced readers to consider how they read Fantasy.

Let’s consider the narrative beats of The Beginning Place:

Two main characters have awful lives. They are taking no action to find freedom or agency.

They discover a fantasy world where they can momentarily pretend their real life problems don’t exist.

They want to commit further to this world, become heroes, stay, and find love.

The Fantasy world betrays them and uses them for its own purposes, proving it undependable.

Instead of slaying the monster for the villagers, they slay it for themselves, finding and proving their own strength.

They recognize the newfound strength in each other and ally to face the world.

They return home ready to take ownership of their lives.

You see what Fantasy fans would find missing here?

They’re looking for a consuming, powerful world and narrative they can get lost in.

Brian Atterbery wrote in a journal article in 1982 that “in [Hugh and Irene’s] actions and reactions Le Guin embodies her notion of the ways fantasy can be used either to evade or to achieve psychological growth.”

And this is exactly it:

The moral of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Beginning Place is that Fantasy is an opportunity to find strength to return to the real world to face your real problems. It should not and cannot be used as a means to forever avoid them. At some point, the fantasy world will let you down, and you will still have your problems to face.

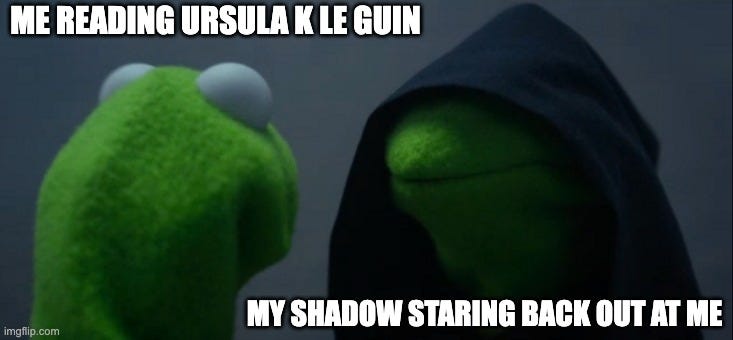

And interestingly, UKLG was a fan of Carl Jung who taught a model of the human psyche that included the “shadow,” a sort of dark spot in our mental makeup where all our repressed stuff and evil tendencies go.

In her essay “The Child and the Shadow” (1974), Le Guin describes it as “all we don’t want to, can’t, admit into our conscious self, all the qualities and tendencies within us which have been repressed, denied, or not used.” She explains that to exist in the world as an adult, one must admit their shadow’s existence and admit that “the hateful, the evil, exists within myself.” Doing this is the first step toward understanding one’s self and others, and was an important part of her fiction writing process.

Defending her choice of genre for this goal, she wrote that “fantasy is the natural, the appropriate language for the recounting of the spiritual journey and the struggle of good and evil in the soul” because it lends itself to the the confronting of the shadow.

And the purpose of The Beginning Place comes into focus when we read further into “The Child and the Shadow”: “what we need to grow up is reality, the wholeness which exceeds human virtue and vice. We need knowledge; we need self-knowledge. We need to see ourselves and the shadows we cast.”

Blatantly, then, the monster that Hugh and Irene conquer is their own individual shadows. The hint is there. Irene sees it as a female, but Hugh contradicts her and is about to say that she’s wrong—it’s male. The fantasy world of Tembreabrezi and what they’ve experienced there lead them to their shadow. They almost run back to their own worlds but instead they conquer the dark part of themselves, gaining wisdom and agency.

As Le Guin writes in “The Child and the Shadow,”

“For we can face our own shadow; we can learn to control it and to be guided by it; so that when we grow into our strength and responsibility as adults in society, we will be less inclined, perhaps, either to give up in despair or to deny what we see, when we must face the evil that is done in the world and the injustices and grief and suffering that we all must bear, and the final shadow at the end of all.”

Irene and Hugh conquer their shadow and return stronger to their home world. They are no longer young people but adults. They know what they want. They will try for it even if they don’t know how to accomplish it yet.

But Le Guin implies that someone who reads Fantasy literature and never bothers to learn from it or to confront their own Shadow through it loses a chance at self-knowledge and thus truth and thus strength to face a difficult world full of evil.

As Atterbery writes, “Another of Le Guin's points about fantasy, is that it is, despite parallels, not the same as waking life and should not be experienced in the same way. To do so is to trivialize it. . . . Both Hugh and Irene are guilty at first of this misunderstanding or misusing of the fantasy experience.”

And that’s what serious, longterm escapism is—a misuse of a wonderful genre with near unlimited power to help us understand ourselves and the real world better.

The Fantasy genre isn’t actually about other people slaying dragons. It’s meant to help us slay our own, internal dragons.

So if Fantasy doesn’t leave you more invested in the real world, you’re reading it wrong. And you might need to read The Beginning Place, a “boring” novel that’ll teach you the true power of Fantasy.

Thank you for reading past the dragon.

If you’d like to read a similar essay about Ursula K. Le Guin, I present the following to you:

In it, Le Guin takes a sledgehammer to sell-outs, and it’s beautiful. The lady knew no fear and had a real talent for calling people out. Enjoy!

Also, I have to forgive myself for how long this post ended up being. I wanted to write a tidy, little 1,000-word essay about one of my favorite novels, and it kept getting longer and longer. I cut out a lot, but still… I have a real problem. Hopefully you feel as though I did The Beginning Place and Ursula K. Le Guin justice.

A question for you: What is your favorite novel you’ve ever read that calls out or makes fun of the Fantasy genre? I’m always looking to add to my Thriftbooks wishlist.

Join me for my next essay in which I’m going to copy in all 90 of the one-star reviews of The Beginning Place from Good Reads and just scream at these people in all-caps for 3,000 words.

I really appreciated a review by Kirkus Reviews that called it “an impeccable parable—and some of the best work ever by a humane, high-minded, underappreciated novelist.” At least someone knows what they’re doing.

Thank you, Brandon Sanderson, for the world’s first metallurgic-gastrointestinal magic system.

I checked, and no one has created fan art of this creature to date. Google’s AI image creator refused to try. Me asking it to was my way of giving AI a middle finger anyway.

Writing like this is usually reserved for literary fiction, but you see it in Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, which is a beautiful diamond of a book too. But I really think we should be ready for a new wave of literary fiction. Smutty romantasy and bloated high fantasy are currently breaking our brains, and reactions always follow. I think really good (although maybe very esoteric?) fiction is coming!

If you want to read more about the development of Fantasy literature over the years, you can check out this article of mine:

The truly most disappointing fantasy novel ever was Wise Man’s Fear. What a stinker, especially after the delight that was The Name of the Wind.

I don't know if you've ever read Diana Wynne Jones (if you haven't you've got a treat in store!) but she often poked fun at genre conventions. This was most obviously done in Dark Lord of Derkholm, in which the fantasy world is tired of hosting quests and pushes back. Its sequel, The Year of the Griffin, shows them rebuilding their world. DWJ also wrote The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, a travel guide (not a story) and a great piece of humor.